9 What’s That Supposed to Mean? Using Feedback on Your Writing

Jillian Grauman

Overview

Providing feedback to students is one of the most challenging parts of a composition instructor’s job (Caswell; Straub, Practice), and making use of that feedback (whether provided by a professor, tutor, or classmate) is just as challenging for students.[1] While research has shown that students prefer feedback that helps them to revise some substantial part of their paper (Haswell; Lizzio and Wilson), they don’t always receive this kind of feedback—and even when they do, many students still tend to have a difficult time making revisions. This chapter 1) helps students understand that having difficulty using and interpreting feedback is normal—that using feedback successfully is actually a learned skill—and 2) presents recommendations students can tailor to their own contexts and goals. It includes four major sections: a personal narrative, an overview of typical challenges, recommendations for using feedback, and student revision examples.

As an early college writer, you have already received lots of feedback on your writing—from high school teachers, college professors, peers, writing tutors. And you already know that you’re supposed to read and use that feedback. But it’s likely that at least some of the time, you looked through your feedback and felt confused. And it’s also likely that at some point the feedback you received hurt your feelings. Maybe the feedback made you feel like a failure. Maybe that feedback confirmed all the things you’ve been telling yourself about your abilities as a writer: “Nope, I’m just bad at this.” Maybe for those reasons, you don’t look very carefully at your feedback—maybe you don’t look at it at all. We all know that reviewing your feedback on your writing is supposed to help you get better, but… how? What exactly are you supposed to do with all that feedback you get on your writing? Especially when that feedback can be hard to implement, frustrating, or hurtful?

I can confidently say that the scenarios I outlined above are pretty common not only because research tells us about them (Babb and Corbett; Batt; Dohrer; Ferris; Haswell; Lizzio and Wilson; Straub Practice; Straub “Students’ Reactions”), but also because I experienced those kinds of things myself as a student.

During my first semester of college, I was excited to get my first college paper back from my professor. I sat patiently at my desk, waiting for my professor to finish handing out our essays. As a high school student, English had always been my favorite subject and my papers had received good grades with few or no comments. When my professor finally handed my paper back, I eagerly turned my paper over, ready to bask in my success. Instead, at the top of the page, I saw a B- written in bright red pen. A B-? Not even a B, but a B-? Feeling totally deflated, I didn’t read any further. I stuffed the essay in my backpack, where it crumpled down to eventually form a clump with other unwanted scraps of paper.

I completely ignored the feedback I received on my very first college essay—an unfortunate decision since feedback is perhaps the most powerful tool for improving as a writer. When taken seriously, feedback can help you to think metacognitively—to think about your own thinking. Composition scholar Howard Tinberg argues that “it is metacognition that endows writers with a certain control over their work, regardless of the situation in which they operate” (76). For example, when your feedback makes you reconsider the way you organized your essay (“Why did I put that idea there?”), you are ultimately building the skills you’ll need to not only revise the paper in front of you, but also to write more effectively in the future; you’ll be better able to transfer your learning into different writing situations.

This chapter is meant to offer you the information and advice I needed as a college student struggling to use my feedback. I’ll go over common challenges with using feedback, recommend steps you can follow to make good use of your feedback, and showcase examples of how real students used their feedback to revise.

Typical Challenges

There are a number of reasons why people have a hard time using feedback on their writing. In this section, I overview typical challenges and how to move past them. The challenges I focus on here are:

- seeing writing ability as an unchangeable character trait

- deciphering your feedback

- deciding whether you have to or should take actions recommended in your feedback

Challenge 1: Seeing Writing Ability as an Unchangeable Character Trait

In the story I told in the introduction, I saw my writing ability as an inherent and unchangeable part of who I was. This kind of thinking is what Carol Dweck calls a “fixed mindset,” which is when you “[believe] that your qualities are carved in stone” (6). If you think your writing ability is “carved in stone” or unchangeable, then what incentive is there for looking through your feedback?

Instead, we should have a “growth mindset” toward our abilities to write, a mindset that measures success by our ability to grow and isn’t steeped in fear of how many mistakes we make (Dweck 17). Essentially, if you understand that you’re not an inherently good or bad writer, but instead a writer who can improve, all of a sudden, the feedback you receive becomes a valuable tool. Composition scholar Shirley Rose emphasizes this point: no matter who you are, “all writers always have more to learn about writing” (59). Even expert writers have to learn and grow as they adapt their writing for new audiences, purposes, and constraints. By seeing ourselves as ever-growing writers, we can embrace revision as an essential part of our learning process and acknowledge that we need practice to improve (Downs 66; Yancey 63). Feedback on our writing is essential to that process.

To craft your own growth mindset, try this strategy recommended by education researcher Saundra Yancy McGuire. Think of a challenge that you have overcome in the past—any challenge at all. Whether it was learning to ice skate, bake sourdough bread, or create a resume, all of these tasks may have seemed out of reach, but with time and practice got easier, right? The same thing is true for academic challenges, like writing papers.

If you’ve improved before, you can do it again. Remind yourself of your past successes!

Challenge 2: Deciphering Your Feedback

Feedback should help you grow as a writer. But how exactly you’re supposed to grow can be ambiguous—if not totally confusing. It can be difficult to make sense of all the different comments you may get and what they are saying. Luckily, comments on writing tend to fall into some broad categories, and if you can figure out what kind of comment you have, then you can figure out what to do with it. We’ll discuss different forms of feedback first and then the content of your feedback.

Forms of Feedback

The feedback you get on your writing can take a lot of different forms. Depending on the situation, you may get verbal feedback accompanied by some notes from a writing tutor, a screen recording of your professor reading through your paper and verbalizing their thoughts, written comments in the margins of your draft from a peer reviewer, or anything in between. No matter the mode of feedback though, your feedback is going to generally be either “local” or “global.” According to Richard Straub, local feedback focuses on a specific part of your paper, topics like grammar or mechanics (“Students’ Reactions”). Global feedback focuses on aspects of your writing that impact the entire paper, like your organization or idea development.

When you receive written feedback on your writing, it may take the following forms:

- In-text or marginal comments: Found in the margins of your paper, this kind of feedback is typically brief and may focus on local or global issues.

- End note or terminal comments: Found at the very beginning or end of the draft (or accompanying it), this kind of feedback is typically written as a letter to the author and tends to focus on global issues.

- Rubric: Found at the very beginning or end of the draft (or accompanying it), this kind of feedback evaluates how well you achieved the assignment criteria and tends to focus on global issues.

The form of the feedback indicates what you may need to do with it, but we also need to understand the content of your feedback.

Content of Feedback

Sometimes feedback is confusing or overwhelming because we’re just not sure about its purpose. Thankfully, Summer Smith broke down the purposes of comments into three general categories: comments that judge some aspect of your writing, coach you on some aspect of your writing, and react to the paper. We should probably add an other category, comments that are too confusing or vague to decipher. Once you get a handle on the purpose of your comments, you can make better decisions about what to do with them.

Judging Comments

Judging comments are an assessment of how well you are doing a particular thing. That assessment can be positive (praise) or negative (criticism). Below is an example of both a positive and negative judgment.

- Positive: This is a concise thesis statement that clearly shows the purpose of your letter.

- Negative: This transition is confusing.

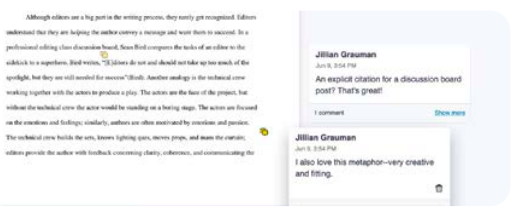

You can see another example of what a positive judgment looks like from an actual student paper in figure 1.

You may think of praise as a waste of time (“Just tell me what to do!”), but it is helpful for learning where your strengths lie—and intentionally replicating that success elsewhere. If you’ve got a negative judgment, or critique, you know there’s at least one thing you may want to revise. If, like in the bulleted example above, the comment notes a confusing transition, that may encourage you to reconsider how your different ideas fit together.

Coaching Comments

Coaching comments offer suggestions. Research (Haswell; Lizzio and Wilson) tells us that students most prefer this feedback because it helps with making immediate changes to a paper. Below are examples of coaching comments:

- Suggestions: Use paragraphs to better sequence and group the information for the reader.

- Questions: Why talk about Snapchat now?

You can see another example of what a coaching comment looks like from an actual student paper in figure 2.

Sometimes coaching comments are written indirectly, as questions. These questions may feel frustrating since they don’t usually come with instructions, but an important thing that questions do is keep you in charge of your writing. Lil Brannon and C. H. Knoblauch explain that students have a right to compose their work as they wish, so your reviewer is not presuming to know what to do best, but instead leaving that decision to you, the author (158).

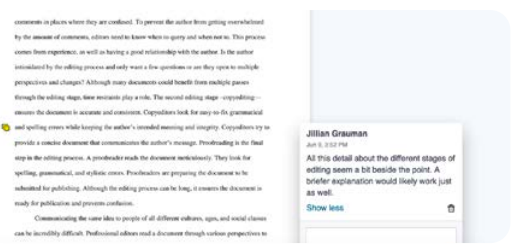

Reacting Comments

Reacting comments explain your reviewer’s understanding of the paper or reactions to your writing. Here are some examples:

- Explaining understanding of the paper: I thought this paragraph was focusing on the typical audience of this genre, but now we have this new idea.

- Offering personal connection: Wow—starting middle school in the US while learning English is impressive.

Find another example of a reacting comment from an actual student paper in figure 3.

When you encounter comments that explain the reader’s understanding of the paper, you may be inclined to shrug your shoulders and say, “Ok, whatever—moving on!” But don’t do it! These are some of the most helpful bits of feedback you can receive on your writing because they give you a window into your readers’ thoughts as they were reading. If, as in the example above, the reader noted something they thought was unexpected, you can consider the impact you wanted your writing to have and whether it aligns with this reaction. If it’s not, you will need to revise accordingly.

Other Comments

Finally, we come to other comments, comments that are too vague or confusing to understand. Here are a couple examples of other comments:

- ?

- Awk

While it is tempting to just ignore these comments, follow up with them instead! It’s possible that these comments might make you feel sheepish. “Well, I’m supposed to know what this means, but I don’t, so there must be something wrong with me.” That is not the case. Sometimes reviewer feedback can just miss the mark, so there’s nothing wrong with asking questions about your feedback. Ask your reviewer what they meant and have a conversation about the implications. For example, if that lone question mark in the margins was meant to indicate confusion, ask what the reader found confusing. If you’re not able to approach your reviewer, take your work to the writing center. They can help you decipher unclear comments (and offer their own helpful feedback).

Challenge 3: Deciding Whether You Have to or Should Take Recommendations in Your Feedback

Another set of challenges has to do with acting on the feedback you get. Consider this scenario: You leave peer review with one partner saying that you did a great job on your thesis statement and the other partner telling you that your thesis statement could be clearer. What do you do? Or this one: Your professor suggested that you consider reorganizing your paper and developing one of your main points further. That sounds hard—and you’re not so sure about developing that idea further. You didn’t think it was all that important to your paper. Do you have to make all those changes? Should you? Underpinning the questions about these scenarios is an important fact: you are the author of your work, so you get to make the final call. No matter where your feedback comes from, you need to make your own decisions about what the best action is.

Some people go into revision thinking that writing is completely subjective. “There are no rules here, so I’ll just do whatever the professor tells me to do.” In this way of thinking, all feedback authors are equally random, but some are more powerful than others (professors > peers), so you just go along to get along. However, writing isn’t random, and writing just to please your reviewer isn’t going to help you develop your writing skills. Your feedback may have felt random in the past because your reviewers made different assumptions about your intentions—and while your professor is an expert on effective writing, your professor is not automatically an expert on what you were trying to get across. Back in 1982, Brannon and Knoblauch argued that when providing feedback, professors should ensure that they value students’ intentions in their writing and not assume they know what the student was trying to do. In other words, you have the right to control your own text.

You don’t need to take all suggestions offered to you—especially if they run counter to your goals. Rather, you need to decide whether the suggestions align with what you want to accomplish. If it seems like your aims didn’t come through, that is what you should be revising—not advice based on misunderstanding your intentions, even if that feedback came from your professor! Feedback with specific suggestions can be helpful, but you can’t simply follow a reviewer’s list of suggestions and be good to go. Instead, you need to decide what the best plan is for your intentions in your paper. Rather than taking a suggestion at its word, use it to get a better understanding of how others saw your writing, which can tell you how successful you were. That is the kind of feedback you can do tons with.

Recommendations

So now that we have a better understanding of common challenges with using feedback, let’s tackle how to use that feedback. The next time you get feedback on your writing, try out the following steps to help you figure out what to do and how to do it:

- set your own goals

- review the feedback

- acknowledge emotional responses

- develop follow-up questions

- act on your goals

1. Set Your Own Goals

Before you even start working with your feedback, consider what you want to do with it. It may be tempting to just say, “Well, I just want to make my paper better,” but keep in mind that growth mindset concept from earlier. One way to develop a growth mindset and see yourself as a writer who always has more to learn is to reflect on what you want to learn from the feedback, to establish your own intentions. Debra Myhill and Susan Jones argue that this kind of reflective thinking is essential to effective revision. Taking a moment to set your own goals is an example of the kind of metacognitive, reflective thinking that will help you transfer your learning to different writing situations.

A key part of setting your own goals is to, of course, review your paper. Take some time to read your draft (without any comments) to remind yourself of what you actually said and did. With your paper fresh in your mind you can then, as Sandra Giles recommends, consider what your intentions were with the paper (198). Were you trying to persuade, define, or analyze? How effective do you think you were? You can also consider which parts of your essay you were most concerned about others reviewing and set a goal related to that. Keeping in mind that the type of paper you’re writing and the part of the semester you’re in should matter, goals might look like the following:

- I want to find out if my reviewer was persuaded by my argument and make my argument more compelling.

- I want to make my paper more interesting, especially my introduction.

You could set many different goals for reviewing your feedback, but the most important thing is that the goals matter to you!

2. Review the Feedback

We learned earlier that your feedback may come in many different forms, but no matter how your reviewer provided it, first make sure that you can find and access that feedback. If you’re not sure where it is or how to get to it, find out as soon as possible. You have my full permission (and urging!) to stop reading this right now so you can figure that out!

Once you’ve got the feedback in front of you, make sure that you go through all of it. Start with any in-text comments. Because these are usually written in response to specific questions or observations the reader had as they were reading through your work, those comments tend to make the most sense if read in context with your paper, so be sure to read your writing around in-text comments. After that, read your end note and rubric.

As you go through all that feedback, take notes and go slowly enough to give yourself time to think. If you have written feedback, consider reading it out loud (or just mouthing the feedback if you feel awkward about talking to yourself) to get yourself to slow down. If your feedback is an audio file or a video, see if your player will let you play it at a reduced rate—try 0.75 speed rather than full speed. Take notes in whatever way works best for you. This could mean marking up your paper with your own comments, typing replies to the comments, writing on a separate sheet of paper, or whatever works for you. Mark any comments that you found confusing or you want to act on later. I also recommend keeping a list of things your reviewer noted that you did well—knowing your strengths is just as powerful as knowing where you can improve.

3. Acknowledge Emotional Responses

Reviewing your feedback can elicit emotional responses—this is totally normal, and your feelings are legitimate! Reviewing your feedback may elicit positive emotions, like feeling proud of yourself, but it can also elicit negative ones, like feeling misunderstood or discouraged. Dana Ferris found that previous experiences with writing in school, whether good or bad, were linked to students’ experiences with professor feedback (25). If you’ve gotten hurtful feedback before, it’s normal for that feedback to stick with you and color experiences with your current feedback.

Whatever you feel, acknowledge those emotions and note which bits of feedback elicited the strongest emotions. Take a moment to ask yourself why that comment had an impact on you and consider how you want to move forward. For example, if you’re feeling upset about a comment because it shows that the reviewer misunderstood you, consider following up with the reviewer. If a comment made you feel great about your future writing potential, maybe you should tell your reviewer that! If a comment was hurtful, that also may be worth telling the reviewer, depending on how comfortable you feel with that. Or maybe you don’t need to do anything more than simply acknowledge what you’re feeling and move on from there.

4. Develop Follow-Up Questions

Once you’ve reviewed your paper, considered your feedback, and taken some notes, it’s time to develop follow-up questions. These questions should help you:

- • Figure out what the comment means

- Clarify what, if anything, should be done in response to the comment

- Explain your intentions and see if knowing that would change the comment

It may be that you’ll actually take these questions back to the reviewer, but it could just as well be that these questions will only be for you. For feedback that you found confusing, the original reviewer could be helpful in figuring out what to do next. However, if it’s not possible to do this or you don’t feel ready to talk to the reviewer, these questions are also great to take to a writing center appointment.

5. Act on Your Goals

Now comes the hardest part—acting on your goals! This may feel overwhelming and challenging. After all, the same researchers who help us understand which comments students most prefer (Haswell; Lizzio and Wilson) also explain that students have a difficult time working with their comments—you’re not alone in finding this step difficult! However, Nancy Sommers, a composition researcher, explains that all revision is basically one of four specific actions: adding, deleting, replacing, and reorganizing (380). No matter how complex or challenging a revision might be, it will ultimately come down to deciding what you need to add, take out, replace with something else, or move around—not so bad.

That being said, Sommers also found that student writers tend to think about revision as just swapping out words and cleaning up errors, so they tended to mostly delete and replace small portions of their work, focusing mostly on local revisions (382). There is nothing wrong with making sure local revisions are taken care of, but when Sommers compared students to experienced writers (people who had written a lot before and wrote as part of their job), she found that the experienced writers used all four revision strategies and focused on big-picture (i.e., global) revisions (386).

In your revision, I encourage you to treat your work the same as these experienced writers did by focusing on global revisions first and trying to make use of all four revision strategies. Use your feedback for guidance on the development of your ideas and how well your organization works. Are there any new ideas that you need to add or develop further? Any ideas or evidence that should be moved? For example, you might look for places where you were offered feedback that shows the reviewer didn’t understand what you were trying to do—is there something you can add or clarify to get your intentions across more clearly? Perhaps you notice that several bits of feedback were about organizational changes—that might indicate you could work on reorganizing or restructuring your body paragraphs, a change that would impact a large chunk of the paper. Once you’ve worked on big-picture issues, return to those local issues. When you’re done revising, use your feedback as a means of checking over your work. Have you addressed all the concerns that you needed to?

Student Revision Examples

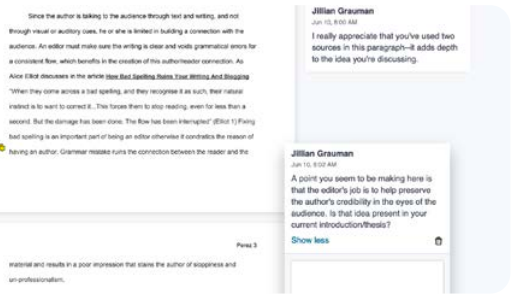

So, what can revision actually look like in practice? Let’s look at how two students, Nicole and Lauren, worked with feedback that they received during a peer review. Both students were tasked with writing a paper that defined and described what a good editor should do. Before their peer review, I asked all authors to describe their concerns and what their reviewers should focus on when providing feedback.

Nicole

In Nicole’s overview of her own work for peer review, she said that she wanted to work on her introduction and conclusion. She wrote, “Introductions and conclusion are not my strongest area, I would love suggestions on how to make them better.”

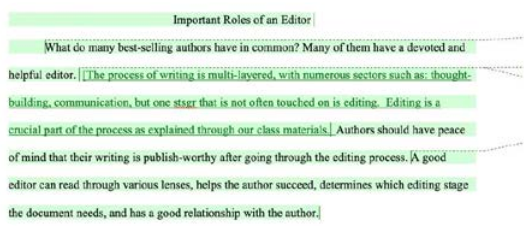

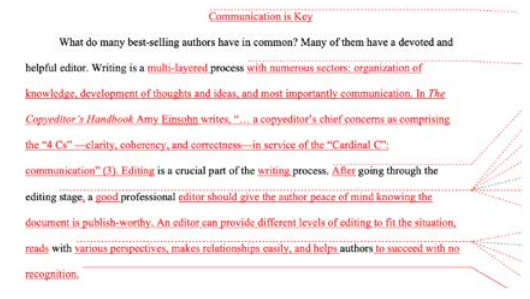

Here’s Nicole’s original introduction paragraph:

Important Roles of an Editor

What do many best-selling authors have in common? Many of them have a devoted and helpful editor. Writing is a process and editing is a crucial part of that process. Authors should have peace of mind that their writing is publish-worthy after going through the editing process. A good editor can read through various lenses, helps the author succeed, determines which editing stage the document needs, and has a good relationship with the author.

Figure 4. Screen capture of the introduction paragraph from Nicole’s initial draft. Image captured by Jillian Grauman.

As you can see, it’s relatively short, and a bit off-focus since much of this paragraph is focused on what authors do, rather than what editors should do. We can also see that she has a thesis statement at the end of this paragraph.

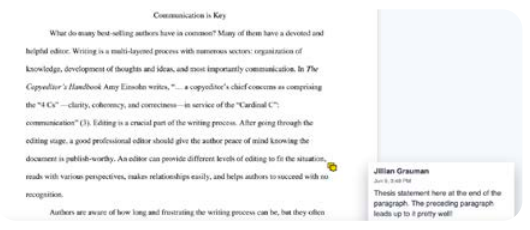

Yonik, one of Nicole’s peer review partners, took Nicole’s concern about her introduction seriously enough to offer some notes on it. Here’s what Yonik had to say:

His first in-text comment is a judgement—a positive one. He praises Nicole’s choice of starting off the paper with a quotation and offers a bit of reassurance by stating that she might be overly negative about her introduction. He later reinforces that positive judgment by noting that the thesis is clear. In the middle of the paragraph, Yonik suggests an idea for expanding on the idea of what editing does. His suggested language includes a reference to materials from the class—a solid suggestion since this assignment required students to include references to class readings and discussions.

The following shows Nicole’s revisions to her original introduction paragraph—what she ultimately submitted as the final draft. The underlined text indicates additions or replacements she made to her peer review draft:

indicated by underlined text. Image captured by Jillian Grauman.

You can see that Nicole followed her own instincts by making a number of changes to the introduction, despite Yonik’s assurances that it was all right. Nicole did take some of his other advice though. She used some of Yonik’s suggested language and took his suggestion to reference work we read in the class.

And finally, below shows my response to Nicole’s introduction in her final draft:

I wrote a reacting comment, a comment that shows how I was understanding her writing, by identifying where the thesis statement is. My intention is to help Nicole check herself against my reading; she can see whether or not I identified her thesis correctly and act accordingly. The second sentence is a positive judgement, recognizing that the previous paragraph does a good job of preparing the reader for that thesis.

Nicole’s work here shows a positive revision trajectory. She started with a draft that received a mix of positive feedback and revision suggestions, and Nicole thoughtfully incorporated the feedback. She trusted her own judgement, made her own revisions, and ultimately ended up with a more developed introduction that better fit the assignment requirements and her own purposes.

Lauren

During her peer review for the same paper, Lauren assessed her work as “half-done and super choppy,” (a perfectly fine way to go into peer review, by the way!) so she needed to work on idea development and organization. Here’s the first part of her peer review draft.

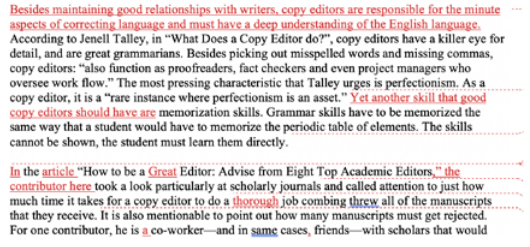

Fellow students in class have compared copy editors to side kicks, ring leaders, and my own comparison, a bar tender. What do these jobs have in common? Leadership skills. Self-Confidence. Authority. A copy editor wears many hats, having skills in grammar, and and eye for language is merely a given.

According to Jenell Talley, in “What Does a Copy Editor do?”, copy editors have a killer eye for detail, and are great grammarians. Besides picking out misspelled words and missing commas, copy editors: “also function as proofreaders, fact checkers and even project managers who oversee workflow.” The most pressing characteristic that Talley urges is perfectionism. As a copy editor, is is a “rare instance where perfectionism is an asset.”

Another interesting tactic that Talley mentions, one in which I had not yet considered, is to be a good copy editor is to teach memorization skills. Grammar skills have to be memorized the same way that a student would have to memorize the periodic table of elements. The skills cannot be shown, the student must learn them directly.

Figure 8. Screen capture of three paragraphs from Lauren’s peer review draft. Image captured by Jillian Grauman.

You can see some of that choppiness between the second and third paragraphs; she moves straight from discussing one source into the next without much of a connection.

During peer review, Nicole took note of Lauren’s concern about the choppiness of the paper. In her end note to Lauren, she wrote:

You also mentioned that it was choppy. I didn’t want to overload the document with comments, so I wanted to say a few general things that might help! When I am writing my own papers, I like to relate the first and last sentences to the prompt/thesis. Also using transitional phrases at the beginning of a paragraph helps me.

Lauren’s final version of the document looks quite different from the original. She added more ideas throughout, and she also worked to smooth out the transitions between the paragraphs, as Nicole suggested.

This was a big improvement, but I did notice some of that original choppiness still hanging on in the final version, which I commented on below.

Similar to Nicole, Lauren’s revisions also show positive change. She identified an issue in her own writing, an issue that her reviewer agreed with, and she made good revisions. While she could still do more to connect her ideas together, the final version showed improvement.

Conclusion

While using feedback on your writing may seem like a pretty straightforward task, it’s actually hard to do well. It’s common to see writing skills as an inherent character trait rather than a skill to develop with time and practice, to have trouble deciphering your feedback, and to be unsure about what to do with your feedback. However, you can get a lot out of your feedback, whether that feedback comes from your instructor, a peer, a tutor, or someone else, with the following steps:

- setting your own goals

- reviewing the feedback

- acknowledging emotional responses

- developing follow-up questions

- acting on your goals

Taking these steps will help you to reflect more and improve on your work as a writer. Working with feedback doesn’t have to be an exercise in disappointment or confusion—instead it can be the most helpful and effective tool you have for developing as a writer.

Works Cited

Babb, Jacob, and Steven J. Corbett. “From Zero to Sixty: A Survey of College Writing Teachers’ Grading Practices and the Affect of Failed Performance.” Composition Forum, vol. 34, 2016, http://compositionforum.com/issue/34/zero-sixty.php.

Batt, Thomas. “Don’t Be Cruel.” Chronicle of Higher Education. 3 Feb. 2016.

Brannon, Lil, and C. H. Knoblauch “On Student’s Rights to their Own Texts: A Model of Teacher Response.” College Composition and Communication, vol. 33, no. 2, 1982, pp. 157-66.

Caswell, Nicole I. “Dynamic Patterns: Emotional Episodes within Teachers’ Response Practices.” Journal of Writing Assessment, vol. 7, no. 1, 2014.

Dohrer, Gary. “Do Teachers’ Comments on Students’ Papers Help?” College Teaching, vol. 39, no. 2, 1991, pp. 48–54.

Downs, Doug. “Revision is Central to Developing Writing.” Naming What We Know, edited by Linda Adler-Kassner and Elizabeth Wardle, Utah State University Press, 2015, pp. 66-7.

Dweck, Carol. S. Mindset: The New Psychology of Success. Random House, 2006.

Ferris, Dana. “‘They Said I Have a Lot to Learn’: How Teacher Feedback Influences Advanced University Students’ Views of Writing.” Journal of Response to Writing, vol. 4, no. 2, 2018, pp. 4–33.

Giles, Sandra L. “Reflective Writing and the Revision Process.” Writing Spaces: Readings on Writing, edited by Charles Lowe and Pavel Zemliansky, vol. 1, WAC Clearinghouse/Parlor Press, 2010, pp. 191-204.

Haswell, Richard H. “The Complexities of Responding to Student Writing; Or, Looking for Shortcuts via the Road of Excess.” Across the Disciplines, vol. 3, no. 1, 2006, n.p.

Lizzio, Alf, and Keithia Wilson. “Feedback on Assessment: Students’ Perceptions of Quality and Effectiveness.” Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, vol. 33, no. 3, 2008, 263–75.

McGuire, Saundra Yancy. Teach Students How to Learn: Strategies You Can Incorporate into Any Course to Improve Student Metacognition, Study Skills, and Motivation. Stylus Publishing, 2015.

Myhill, Debra and Susan Jones. “More Than Just Error Correction: Students’ Perspectives on Their Revision Processes During Writing” Written Communication, vol. 24, no. 4, 2007, pp. 323-43.

Rose, Shirley K. “All Writers Have More to Learn.” Naming What We Know, edited by Linda Adler-Kassner and Elizabeth Wardle, Utah State University Press, 2015, pp. 59-61.

Sommers, Nancy. “Revision Strategies of Student Writers and Experienced Adult Writers.” College Composition and Communication, vol. 31, no. 4, 1980, pp. 378–88.

Smith, Summer. “The Genre of the End Comment.” College Composition and Communication, vol. 48, no. 2, 1997, pp. 249–68.

Straub, Richard. Practice of Response. Hampton Press, 2000.

Straub, Richard. “Students’ Reactions to Teacher Comments: An Exploratory Study.” Research in the Teaching of English, vol. 31, no. 1, 1997, pp. 91–119.

Tinberg, Howard. “Metacognition is not Cognition.” Naming What We Know, edited by Linda Adler-Kassner and Elizabeth Wardle, Utah State University Press, 2015, pp. 75-6.

Yancey, Kathleen Blake. “Learning to Write Effectively Requires Different Kinds of Practice, Time, and Effort.” Naming What We Know, edited by Linda Adler-Kassner and Elizabeth Wardle, Utah State University Press, 2015, pp. 64-5.

Teacher Resources for What’s That Supposed to Mean? Using Feedback on Your Writing

Overview and Teaching Strategies

This essay can frame your class conversation around revision practices, peer review, and teacher feedback. I recommend reading this essay early in a composition class, ideally before the first peer review and before students receive substantive teacher feedback. Familiarizing students with strategies on how to use their feedback before they receive any will help prepare them for taking their feedback seriously and using it to improve as writers. This essay would also work well at the beginning of a unit or major assignment with a heavy revision component.

Many of the discussion questions offered below would work well either before or after reading the essay. You may want to ask students to consider their current feedback practices before reading the essay so they can more effectively compare strategies and reflect on how the strategies would work for them.

If you have students read this essay before receiving any feedback, I recommend doing Activity 1 on the day you discuss the essay. Once students receive feedback (either from peers or you), I recommend doing Activity 2 or 3 to help students better incorporate the strategies into their own writing practices. If you have students read this essay after receiving feedback, I recommend doing either Activity 2 or 3 on the day you discuss the essay.

Discussion Questions

- Do you believe you have a fixed or growth mindset about your writing abilities? Why or why not? What could help you grow as a writer?

- What sorts of emotions do you experience or have you experienced while receiving feedback from others on your writing? How does that impact your revision process?

- What do you typically do when you receive feedback on your writing from a teacher? From a peer? From a writing center tutor?

- What do you think you should do with your feedback? Is that different from what you typically do?

- In a perfect world, what would your writing feedback help you do?

Activity Ideas

Activity 1: Have students look at feedback they received on a piece of their writing from a previous class or writing situation. For students who can find an example, have them consider what they did with this feedback. What more could they have done—or what else could they have done with it? For students who can’t find an example, have them consider why they can’t find this kind of material. Why don’t we tend to hold on to the feedback we receive on our writing?

Activity 2: Have students locate and review recent feedback you have provided them on their writing. Ask students to:

- Identify which comment they found most useful and why

- Identify which comment they found least useful and why

- Identify which comment they found most confusing

Activity 3: Ask students to follow the recommended steps in this chapter for using feedback after a peer review or receiving feedback from the instructor and write about or discuss that experience in class. Students would discuss/write about:

- Goals they had for the feedback

- Emotional responses to the feedback

- Follow-up questions

- Actions they took with the feedback

- Similarities and differences between this process and their previous strategies for using feedback

- This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) and is subject to the Writing Spaces Terms of Use. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/, email info@creativecommons.org, or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA. To view the Writing Spaces Terms of Use, visit http://writingspaces.org/terms-of-use. ↵