13 Make Your “Move”: Writing in Genres

Brad Jacobson; Madelyn Pawlowski; and Christine Tardy

Overview

When approaching new genres, students often wonder what kind of information to include and how.[1] Rhetorical moves analysis, a type of genre analysis, offers a useful, practical approach for students to understand how writers achieve their goals in a genre through various writing strategies. In this chapter, we introduce students to moves analysis, first describing what it is and then explaining various strategies for analyzing moves. The chapter walks students through moves analysis with both a familiar low-stakes genre (student absence emails) and a less familiar professional genre (grant proposals), demonstrating how such an analysis can be carried out. The goal of the chapter is to familiarize students with rhetorical moves analysis as a practical tool for understanding new genres and for identifying options that can help writers carry out their goals.

I f you are like most students, you’ve probably had to miss a class at some point. Maybe you were sick, stayed up too late the night before, or just weren’t prepared. When you’ve found yourself in this situation, have you emailed your professor about your absence? If so, how much information did you share? Did you include an apology, or maybe an explanation of how you plan to make up any missed work?

You may not realize it, but the email written to a teacher in this situation can be considered a genre. You’ve probably heard the term genre used in relation to music, film, art, or literature, but it is also used to describe non-literary writing, like the writing we do in our personal lives, at school, and at work. These genres can be thought of as categories of writing. These categories are based on what the writing is trying to do, as well as who it is written for and the context it is written in (Dirk; Miller). For instance, a condolence card or message carries out the action (or goal) of sharing your sympathy with someone. A student absence email lets a teacher know about an absence and might also request information for how to make up a missed class.

You encounter many genres every day. In your personal life, these might include to-do lists, menus, political ads, and text messages to schedule a get-together. In school, you may write in genres like proposals, lab reports, and university admission essays. People in professions often write in highly specialized genres: nurses write care plans; lawyers write legal briefs; scientists write research articles, and so on. (For a more in-depth introduction to the definition and functions of genre, check out Dirk’s “Navigating Genres” chapter in Writing Spaces Vol. 1.)

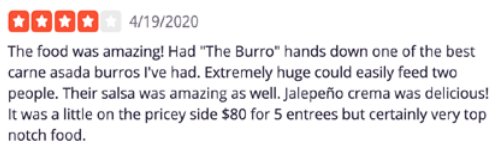

Texts within a genre category aren’t identical, but they often resemble each other in many ways. For example, they might use similar kinds of vocabulary and grammar, design features, content, and patterns for organizing their content. Because of these resemblances, we can often recognize texts as belonging to a particular genre—as in figure 1.

If you recognized this text as a consumer restaurant review, you likely have read similar reviews before, and you’ve started to get a sense of what they “look like.” This is how genres work: When we repeatedly encounter texts within a genre, we get a sense of the language and content they tend to use, as well as how they arrange that language and content. Successful writers have a good idea of how to write effectively in particular genres— this means satisfying readers’ expectations for the genre but maybe also making a text fresh and interesting. Can you think of a time you had to write in a new or unfamiliar genre for the first time? You might have gotten stuck with where to start or what to include. Writing in a new genre can be hard if you don’t yet know the expectations for content, language, and organization. In this chapter, we’ll share a specific strategy that can help you through these kinds of challenges. More specifically, we will look at how to identify and analyze the rhetorical moves of a genre.

What Are Rhetorical Moves?

Most likely, the term rhetorical moves is new to you. It may sound intimidating, but it’s just a (sort of) fancy phrase to describe something you probably already do. Rhetorical moves—also just called moves—are the parts of a text that carry out specific goals; they help writers accomplish the main action of the genre (Swales). For example, a typical wedding invitation in the United States includes moves like inviting (“You are invited to attend…”) and providing venue information (“…at the Tucson Botanical Gardens”). These moves are necessary to carry out the genre’s main action; without an inviting move, an invitation could easily fail to accomplish its goal, and without a providing venue information move, attendees won’t know where to go! A wedding invitation can also include optional moves like recognizing parents (“Jordan and Jaime Taylor request your company at…”) or signaling appropriate attire (“Black tie optional”). Optional moves often respond to specific aspects of a situation or give writers a way to express certain identities or personal goals. Wedding invitations in different countries or cultural communities can have different common moves as well. In China, for example, wedding invitations often include the character for double happiness (囍).

Even a text as short as a restaurant review can include multiple moves. The main action of a restaurant review is to tell other people about the restaurant so that they can decide whether to eat there or not, so the moves that a writer includes work toward that goal. The review in Figure 1 includes three moves:

- evaluating the restaurant overall (“The food was amazing!”)

- evaluating specific dishes (“…one of the best carne asada burros I’ve had…,” “Their salsa was amazing…”)

- providing details about the price (“It was a little on the pricey side…”)

After looking at just one restaurant review, we don’t really know if these are typical moves or if they are just unique to this one consumer’s review. To understand what moves are common to consumer restaurant reviews (which might be a bit different than professional restaurant reviews), we need to look at many examples of texts in that genre. As a writer, it can be very useful to look for moves that are required (sometimes called obligatory moves), common, optional, and rare. You can also think about moves that never seem to occur and consider why that might be the case. For example, have you ever seen a wedding invitation mention whether this is someone’s second (or third) marriage? Or that mentions how much the wedding is going to cost? Those particular moves would probably confuse some readers and not help achieve the goal of the genre!

Analyzing Rhetorical Moves

Analyzing rhetorical moves is the process of identifying moves in multiple samples of a genre, looking for patterns across these texts, and thinking critically about the role these moves play in helping the genre function. To get started with moves analysis, you just need a few strategies we’ll show you throughout the rest of this chapter. We ourselves have used these strategies in situations where we had to write in unfamiliar genres. As a new professor, Madelyn recently had to write her first annual review report—a document used to track her career progress. The instructions she was given were a bit vague and confusing, so she gathered samples of annual reviews from her colleagues to get a better sense of the typical length and type of content included in this genre. One sample she looked at used an elaborate chart, which made her quite nervous because she had no idea how to make this kind of chart for her own report! But after realizing that this chart was not included in the other samples, she decided this move was probably optional and decided to not include it. In this case, understanding the typical moves of the annual review report helped Madelyn avoid unnecessary stress and feel confident her report would meet readers’ expectations.

Before trying to figure out a complicated or unfamiliar genre, it will help to practice first with something familiar like a student absence email. Having received hundreds of these emails as professors (and written a few ourselves), we know this genre is characterized by some typical rhetorical moves as well as a great deal of variation. Let’s walk through the process of carrying out a rhetorical moves analysis.

Identifying Typical Moves of a Genre

The emails in Table 1 were all written by college students (referred to here by pseudonyms). We only share four samples here, but it’s better to gather 5-10 or even more samples of a genre to really get a sense of common features, especially when you are working with a more complex or unfamiliar genre. To identify typical rhetorical moves, first, you’ll want to identify the moves in each individual text you collect. Remember that a move is a part of the text that helps the writer carry out a particular function or action. For this reason, it is helpful to label moves with a verb or an “action” word. When you sense that the writer is doing something different or performing a new “action,” you’ve probably identified another rhetorical move. A move can be one sentence long, an entire paragraph, or even longer, and your interpretation of a move might differ from someone else’s interpretation. That’s okay!

Rhetorical moves in four sample absence emails

Sample 1

Dear Dr. Pawlowski,

[1] I just wanted to tell you that I will be absent from class today. [2] I have completed my mid-term evaluation and I have started my annotated bibliography. If I have any other questions I will ask my study partner! [3] Thank you, and I will see you on Friday!

Sincerely,

Jay Johnson

Sample 2

Dear Professor,

[1] I am sorry but [2] today I am missing class [3] because I have to take my cat to the vet due to an emergency. [4] Could you let me know what I need to do to make up the missed material? [5]

Thank you for your understanding,

Layla

Sample 3

Good morning,

I hope you had a wonderful spring break. [1] I am still experiencing cold symptoms from the cold I caught during the start of spring break. It was mainly from digestive problems (bathroom issues) coming from medication that [2] I had trouble coming to class yesterday. [3] I would like to apologize for any inconvenience I might have caused.

[4] I am continually working on the final assignment that is due tomorrow. [5] If I am not able to turn it in on time, could I possibly have a 24 hour extension? If not, I understand. [6] Thank you as always and I hope to see you tomorrow.

Best Wishes,

Corey M.

Sample 4

Hi,

[1] Sorry but [2] I won’t be in class today.

Ali

Look at how we labeled the moves in these four samples. We did this by first reading each sample individually and thinking about how different parts achieve actions. We then labeled these parts with verb phrases to describe the writer’s moves. In some texts, multiple sentences worked together to help the writer accomplish a particular goal, so we grouped those sentences together and labeled them as a single move (notice move 2 in Sample 1). Sometimes we found that a single sentence helped to accomplish multiple goals, so we labeled multiple moves in a single sentence (notice Sample 4). Don’t worry if you feel like you aren’t locating the “right” moves or labeling them appropriately; this is not an exact science! You might choose different labels or identify more or fewer moves than someone else analyzing the same samples. To find a fitting label for a move, it’s helpful to ask, “What is the writer doing in this part of the text?” To keep consistency in your labeling, it might also help to ask, “Have I seen something like this before in a different sample?” Looking at how we labeled the moves, would you agree with our labels? Do you see any additional moves? Would you have broken up the samples differently?

After identifying moves in individual samples, the next step is to compare the samples, looking for similarities and differences to better understand what moves seem typical (or unusual) for the genre. Based on our labels in Table 1, what moves do you see most and least frequently? A table is useful for this step, especially when you are working with longer or more complex genres and want to visualize the similarities and differences between samples. In Table 2, we listed all of the moves found in the four samples, noted which samples included each move, and decided whether each move seemed obligatory, common, optional, or rare for this particular genre based on how often it appeared. If we noticed the move in every sample, we labeled it as “obligatory,” but if we only saw a move in one or two samples, we figured it might be more optional or rare. We need to be careful, however, about making definite conclusions about what is or is not a typical feature of a genre when looking at such a small set of texts. We would probably locate many more moves or develop a different analysis with a larger sample size. Nevertheless, check out our findings in Table 1.

| Move | S. 1 | S. 2 | S. 3 | S. 4 | Obligatory, common, optional, or rare? |

| Informing the teacher that an absence occurred/will occur | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Obligatory |

| Apologizing for absence | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Common | |

| Explaining reason for absence | ✓ | ✓ | Common | ||

| Requesting an accommodation | ✓ | Optional or rare | |||

| Requesting information about missed material | ✓ | Optional or rare | |||

| Taking responsibility for missed work | ✓ | ✓ | Common | ||

| Expressing gratitude | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Common |

Understanding How Moves Help Carry out the Genre’s Social Actions

We now want to consider how certain moves help the genre function. Start by asking yourself, “What does the genre help the readers and writers do?” and “How do certain moves help carry out these actions?” Keep in mind that a genre may serve multiple purposes. You might send an email to excuse yourself from an upcoming class, to explain a previous absence (see Sample 3), ask questions about missed material (see Sample 2), to request an extension on an assignment (see Sample 3), and so on.

Based on Table 1, at least one move could be considered essential for this genre because it is found in all four samples: informing the instructor about an absence. This move helps the writer make the purpose of the email explicit. Sometimes this simple announcement is almost all that an absence email includes (see Sample 4). Can you imagine trying to write an absence email without mentioning the absence? Would such an email even belong in this genre? Along with a general announcement of the absence, students often include information about when the absence occurred or will occur, especially if they need more information about missed material.

Some of the moves we labeled as optional or rare in Table 2 are not necessarily ineffective or inappropriate, but they might not always be needed depending on the writer’s intentions or the context of the missed class. Sample 2 includes a request for information about missed material, and Sample 3 includes a request for an accommodation. Do the emails with requests leave a different impression than the samples without? Do the writers of requests carry them out in similar ways?

We could continue going through each move, looking for patterns and considering rhetorical effects by asking a) why each move is typical or not, b) what role each move plays in carrying out the genre’s purpose(s), and c) how and why moves are sequenced in a particular way.

Identifying Options and Variations in Moves

Variation across genre samples is likely to occur because of differences in context, audience, and writers’ preferences. But some genres allow for more variation than others. If you’ve ever written a lab report, you likely received very specific instructions about how to describe the materials and methods you used in an experiment and how to report and discuss your findings. Other school genres, like essays you might write in an English or Philosophy course, allow for more flexibility when it comes to both content and structure. If you notice a lot of variation across samples, this might mean that the genre you are looking at is flexible and open to variations, but this could also indicate that you need to label the moves more consistently or that you are actually looking at samples of different genres.

Based on our observations and analysis, the student absence email appears to have some degree of flexibility in both content and organizational structure. There is variation, for example, in how detailed the students are in providing a reason for their absence. Sample 2 mentions an emergency vet visit, providing just enough detail to show that the absence was justifiable and unexpected. Sample 3 also includes an explanation for the absence, but the writer chose to include a far more personal and detailed reason (a cold caught on spring break and bathroom issues from medication? Perhaps TMI (too much information)?). There is also a great deal of variation in the structure of the emails or the sequence of moves. In Sample 3, the student doesn’t mention their absence until the third sentence whereas all the other writers lead with this information. What other differences do you see? How do you think a professor would respond to each email? Understanding your options as a writer and learning how to identify their purposes and effects can help you make informed choices when navigating a new or unfamiliar genre.

Identifying Common Language Features

Writers make linguistic choices to carry out moves, and oftentimes you’ll find similarities across samples of a genre. While there are seemingly infinite features of language we could analyze, here are some to consider:

- verb tense

- passive/active voice

- contractions (e.g., it’s, I’m, we’re, you’ve)

- sentence types

- sentence structures

- word choice

- use of specialized vocabulary

- use of pronouns

To dig deeper into the linguistic features of moves, we could take a few different approaches. First, we could view the genre samples side-by-side and look for language-level patterns. This method works well when your genre samples are short and easy to skim. We noticed, for example, that all four student absence emails use first-person pronouns (I, me, my, we, us), which makes sense given that this genre is a type of personal correspondence. Would it be possible to write in this genre without using personal pronouns?

Our analysis could also focus on how language is used to carry out a single move across genre samples. Using this method, we noticed that in both of the samples that included requests to the teacher, the students use the auxiliary verb could to make their requests. In Sample 2, Layla asks, “Could you let me know what I need to do to make up the missed material?” In Sample 3, Corey asks, “Could I possibly have a 24-hour extension?” There are other possibilities for phrasing both questions more directly, such as “What do I need to do?” or “Can I have a 24-hour extension?” Why might it be beneficial to phrase requests indirectly in this genre?

You don’t need to be a linguistic expert to analyze language features of a genre. Sometimes all it takes is noticing a word that seems out of place (like the use of the greeting “Hi” instead of “Dear Professor”) or finding a phrase that is repeated across genre samples. Or you might start with a feeling you get while reading samples of a genre: the samples might generally feel formal or you might notice a humorous tone. Noticing language features helps you more closely analyze how certain moves are carried out and to what effect.

Critiquing Moves

To critique means to offer a critical evaluation or analysis. By critiquing a genre, we are doing more than identifying its faults or limitations, though that can certainly be part of the process. We might also look for potential strengths of the genre and possibilities for shifting, adapting, or transforming it. The use of the greeting “Hi” in Sample 4 could be an interesting start to a critique about how formal this genre is or should be. While we understand why some professors find it too informal to be addressed with a “Hi” or “Hey,” we also see this move as evidence of how the genre’s norms and expectations are seemingly changing. We personally don’t find these greetings as jarring or inappropriate as we might have 5-10 years ago. Our reactions might have to do with our individual teaching styles, but email etiquette may also be changing more broadly. To pursue this line of inquiry, we could collect more samples of student emails written to other professors and maybe even talk to those professors about their reactions to informal email greetings. Or we could talk to students about why they choose to use formal or informal greetings in these emails. To conduct a critique or analysis of a genre, it is sometimes useful to gather more samples or more information about the context in which the genre is used. Talking to actual users of the genre is often especially useful (see how Brad’s students did this in the next section). Here are some questions to get you started on a critique of rhetorical moves (some have been adapted from Devitt, et al.’s Scenes of Writing):

- Do all moves have a clear purpose and help carry out the social actions of the genre?

- What is the significance behind the sequence of the moves?

- What are consequences for the writer or other users if certain moves are included, or not?

- Who seems to have freedom to break from common moves? Who does not?

- What do the moves suggest about the relationship between the writers and users of this genre? How might this relationship impact the inclusion/exclusion of certain moves?

- What do the moves suggest about the values of a broader community (i.e. a specific class, a specific institution, or the entire educational system of the region)?

Applying Moves Analysis: Writing a Statement of Need

Moves analysis can help as you write in different classes or other personal or professional situations. Let’s take a look at how we can use moves analysis to approach a complicated or unfamiliar genre. You can use the chart in the Appendix as you follow along.

In one of Brad’s writing courses, students used moves analysis when they wrote a grant proposal on behalf of a local nonprofit organization. Grant proposals are common in academic and professional contexts. The goal of a grant proposal (the action it hopes to accomplish) is to convince a funder to support a project or initiative financially. In other words, “give us money!” Each granting agency—the organization with the money—has its own expectations in terms of format, organization, and even word count for proposals, but most include similar sections: a Statement of Need, Objectives for the project, Methods of implementing, Evaluation, and a proposed Budget (“How Do I Write a Grant Proposal?”). We can’t discuss all of these sections here, so in these next few paragraphs, we’ll walk you through a brief moves analysis of just the Statement of Need section (we’ll call it the Statement), just as Brad’s students did.

First, we need to understand what the Statement is hoping to accomplish and why it is important. According to Candid Learning, a support website for grant seekers, a Statement “describes a problem and explains why you require a grant to address the issue” (“How Do I Write”). This section lays out the stakes of the problem and proposes the solution. To learn more about how these Statements work, Brad’s class reviewed several samples from Candid Learning’s collection of successful grant proposals (“Sample Documents”). Let’s take a look at some of the moves students identified in three samples. These proposals were requesting funds for educational development in Uganda (Proposal from Building Tomorrow), an interpreter training center (Proposal from Southeast Community College), and community-based art programming (Proposal from The Griot Project).

Identifying Typical Moves in Statements of Need

First, Brad and his students identified moves in the individual Statements, using verbs to describe them. Then, we compared moves across the samples. Here are three of the moves we found:

Connect Proposal to Broad Social Issue

The writers included statistics or other data from credible sources as a way to establish the need or problem and connect to broader societal issues. Here are a few examples of this move in action:

- UNICEF and USAIDS estimate that 42 million children in this region alone are without access to primary education. (Proposal from Building Tomorrow)

- A study, published in January of 2006 in the journal Pediatrics shows that ad hoc interpreters were much more likely than professionally trained interpreters to make errors that could lead to serious clinical consequences, concluding that professionally trained medical interpreters are essential in health care facilities. (Proposal from Southeast Community College)

Why do you think the writers reference respected sources, like UNICEF, USAIDS, and the journal Pediatrics? Brad’s students thought this move could both help the grant writer build credibility with their reader and show how the project will impact a social problem that goes beyond their local context. We did not see this move in all of the samples, so we’d say this move is common but not necessarily obligatory for this genre.

Demonstrate Local Need

Grant writers have to show the local problem their project is going to solve and why it’s needed. For example:

- Officials in the Wakiso District of Uganda…estimate that 55% of the district’s 600,000 children do not have access to education. (Proposal from Building Tomorrow)

- Statewide, 143,251 people speak a language other than English at home. In Lancaster County, that number is 24,717, up 260% since 1990 (U.S. Census 1990, 2000, 2005). (Proposal from Southeast Community College)

- As community constituents, we have observed a lack of after school and summer enrichment projects that utilize the power of art as a means of community unification. (Proposal from The Griot Project)

Students decided this move is obligatory because it’s in all of the samples. This makes sense because grant writers need to show why their project is important. Referencing outside sources appears to be common within this move, but not required. Why do you think referencing outside sources could be effective, given this move’s role in the genre?

Identify Solution and/or Impact

At some point in the Statement, usually at the end, the grant writer explains how their proposed project will meet the need they identified:

By opening doors to new, accessible neighborhood classrooms, BT can help reduce the dropout rate, provide children with the opportunity to receive a valuable education, and be an instrumental partner in building a better tomorrow. (Proposal from Building Tomorrow)

Brad’s students noticed this move in all of the Statements. Why do you think this move seems to be obligatory?

Understanding How Moves Help Carry out the Genre’s Social Actions

Given what we know about grant proposals and the Statement, these moves seem to be rhetorically effective when sequenced in the order described above: connect to a societal problem, demonstrate local need, and identify a solution or describe the impact of the proposed project. Using these three basic moves helps writers show that their proposed work is important and that they have a plan to solve a problem with the grant money. Understanding the Statement in this way led Brad’s students to conduct further research into issues like food scarcity and access to health care that affected their partner organizations so they could make connections to social issues in their Statements.

Identifying Options and Variations in Moves

The three moves identified were used in most of the grant proposals Brad’s students read. But students did notice variation. Remember that even when moves seem obligatory or common, they won’t necessarily be found in the same order. For example, one proposal identified the local need before connecting to a broader issue, and The Griot Project’s proposal did not include the connecting move at all, instead focusing solely on local knowledge to make their case. Why do you think this might be? Here, it may help to learn more about the audience. The Griot Project’s grant proposal was submitted to Neighborhood Connections, an organization that provides “money and support for grassroots initiatives in the cities of Cleveland and East Cleveland.” When the grant writers say, “As community constituents, we have observed…,” they are localizing their efforts and showing how their project can be considered a “grassroots initiative.” Understanding the audience can be one factor in understanding variation among samples.

Identifying Common Language Features

When students looked across the samples, they noticed personal pronouns like I, we, or us were optional or rare. In fact, the only personal pronoun was in the demonstrating local need move, where one organization referenced their own observation (“we have observed”) to demonstrate the local need. However, they shifted back to third person when identifying the impact (“the Griot Project will improve”), like the other samples. Why do you think the writers included themselves so explicitly in the text when demonstrating the local need, while the rest of the samples maintained a more distant position? What might be gained with this choice, and why might some writers hesitate? Why do you think all of the writers used third person pronouns when identifying the organization’s impact?

Students also noticed a common sentence structure in the identifying move, which we called “By x-ing.” Each of the grant writers used a single sentence and a By x-ing phrase to connect the proposed intervention to an outcome. For example, “By opening doors…BT can help reduce the dropout rate…” (emphasis added). Why do you think this sentence structure seems to be common within this move?

Critiquing Moves

Staff members from an organization supporting economic development on Native American sovereign lands reminded members of Brad’s class that writing a grant proposal means representing an organization and the people and communities it serves. With this in mind, they asked students to emphasize the resilience of the community rather than perpetuate negative stereotypes in the grant proposals; they didn’t want a pity campaign. As a result of this conversation, students decided to highlight local conditions like a lack of grocery stores and access to transportation before introducing statistics about obesity and diabetes rates. They also included pictures of happy families to counter stereotypical images of poverty. In this way, critique of the genre led to subtle, yet important, transformation.

Clearly, a moves analysis like this could go on for a while! Remember, we’re not looking for the “right” answer—we’re trying to understand the options that we have as we begin to contribute our own examples to the genre.

Producing and Transforming Genres using Moves Analysis

Carrying out a moves analysis is more than just an academic exercise. You can use this process whenever you need to write in a new genre. Maybe you are applying for summer internships and you are writing a cover letter for the first time. Instead of starting from what you think a cover letter might look like, you can find several samples and conduct a moves analysis to identify features of this genre. You might also want to try pushing the boundaries a bit. Sometimes, playing with moves or incorporating additional moves in a genre can lead to interesting innovations or new uses for a genre. For each writing situation, you’ll want to decide whether it makes sense to take some risks and be innovative or to stick with more typical approaches. Conducting a moves analysis can be your first step to considering how to carry out your goals, and maybe even expressing your individuality, in a new genre.

Works Cited

Devitt, Amy, et al. Scenes of Writing. Pearson Education, 2004.

Dirk, Kerry. “Navigating Genres.” Writing Spaces: Readings on Writing, Volume 1, edited by Charles Lowe and Pavel Zemliansky, Parlor Press/The WAC Clearinghouse, 2010, pp. 249-262.

“How Do I Write a Grant Proposal for My Individual Project? Where Can I Find Samples?” Candid.Learning, Candid, 2020, learning.candid.org/resources/knowledge-base/grant-proposals-for-individual-projects/.

Hyon, Sunny. Introducing Genre and English for Specific Purposes. Routledge, 2018.

Miller, Carolyn R. “Genre as Social Action.” Quarterly Journal of Speech, vol. 70, no. 2, 1984 pp. 151-167.

“Proposal from Building Tomorrow to Echoing Green.” Candid.Learning, Candid, 2020, https://learning.candid.org/resources/sample-documents/proposal-from-building-tomorrow-to-echoing-green/

“Proposal from The Griot Project to Neighborhood Connections.” Candid.Learning, Candid, 2020, https://learning.candid.org/resources/sample-documents/proposal-from-the-griot-project-to-neighborhood-connections/

“Sample Documents”. Candid.Learning, Candid, 2020, https://learning.candid.org/resources/sample-documents/

“Proposal from Southeast Community College to Community Health Endowment of Lincoln.” Candid.Learning, Candid, 2020, https://learning.candid.org/resources/sample-documents/proposal-from-southeast-community-college-to-community-health-endowment-of-lincoln/

Swales, John M. Genre Analysis: English in Academic and Research Settings. Cambridge University Press, 1990.

Tardy, Christine M. Genre-Based Writing: What Every ESL Teacher Needs to Know. University of Michigan, 2019.

Appendix

Guiding Questions for Analyzing and Using Rhetorical Moves

Identifying typical moves

- Which moves seem obligatory or necessary to achieve the genre’s action(s)?

- Which moves seem common, but not necessary?

- Which moves seem optional or rare?

Identifying how moves help carry out the genre’s actions

- How does each move work to achieve the action or goal of the genre?

- How do the moves work together, given what you know of the typical audience(s), purpose(s), and context(s) of the genre’s use?

Identifying options and variations

- What organizational patterns (sequence, order) do you notice among the moves?

- How do different audiences or contexts seem to affect the moves?

- How do writers use language?

Identifying common language features

- How is language used to carry out the moves you’ve identified? Consider examining:

- verb tense (present, past, future)

- passive/active voice

- contractions (e.g. it’s, I’m, we’re, you’ve)

- sentence types punctuation

- word choice

- use of specialized vocabulary

- use of pronouns

- sentence structures

Critiquing rhetorical moves

- Do all moves have a clear purpose and help carry out the social actions of the genre?

- What is the significance behind the sequence of the moves?

- What are consequences for the writer or other users if certain moves are included, or not?

- Who seems to have freedom to break from common moves? Who does not?

- What do the moves suggest about the relationship between the writers and users of this genre?

- How might this relationship impact the inclusion/exclusion of certain moves?

- What do the moves suggest about the values of a broader community (i.e. a specific class, a specific institution, or the entire educational system of the region)?

Teacher Resources for Make Your “Move”: Writing in Genres

Overview and Teaching Strategies

Rhetorical moves analysis is an adaptable strategy for analyzing, producing, and transforming genres. In this chapter, we walk students through an inductive process that makes visible the ways language choices and writing strategies like organization or structure are connected to the social action of a given genre. Moves analysis is thus a teaching strategy that can help demystify how writing works. Students do not need to have in-depth knowledge of genre theory to conduct a moves analysis, but it will be important for them to understand the concept of genre as social action. This chapter will work well paired with Kerry Dirk’s “Understanding Genres” in Writing Spaces, volume 1, and/or Dan Melzer’s “Understanding Discourse Communities” in volume 3. Connections can also be made to Mike Bunn’s “Reading Like a Writer” in volume 2.

In a sense, conducting a moves analysis in a writing class is similar to what writers at all levels do all the time: gather some samples of work we find effective, try to figure out what specifically makes the samples effective, and then do those things (or transform them) in our own writing. Moves analysis is a flexible strategy that can be introduced when students begin reading a new genre or during their writing process. Christine likes to introduce moves analysis with short familiar genres (like the student absence email example in this chapter), and then return to moves analysis throughout a course when students approach a new genre. Madelyn uses moves analysis to help students identify obligatory, common, optional, and rare genre features as a way of collaboratively negotiating assignment guidelines and expectations, and identified moves become a part of the assessment criteria for student work in a given genre. Brad likes to use moves analysis after students have already written a first draft. After conducting the moves analysis in small groups and identifying some of the obligatory, common, and unusual moves as a class, students can then go back to their draft and make choices based on the analysis.

One of the biggest challenges in facilitating moves analysis is selecting sample texts for analysis. The goal is to identify a narrow enough genre that the texts will be relatively similar, but also flexible enough to show variation. For example, in the student absence emails, we are clearly able to see variation across individual texts, but there are also common moves. If our sample set were broadened to also include faculty absence emails, we would probably start to identify slightly different patterns with moves. Some other shorter examples we’ve used to introduce moves analysis in class include wedding invitations, thank you notes, mission statements, obituaries, and protest signs, among others. If asking students to select their own samples, it will be important to emphasize the difference between a modality (email) and a genre (student absence email).

We also need to acknowledge the concern that moves analysis can reinscribe a prescriptivism or focus on correctness that the field’s pedagogical focus on genre seeks to avoid. However, it’s important to recognize that the textual and discursive borrowing that emerges from moves analysis can provide students with effective rhetorical strategies and an entry point to discuss and critique discourses. Focusing discussion on how moves help to achieve an intended action and why particular moves are effective can also help students see the moves as conventions, not rules. The instructor should select a range of effective samples that demonstrate variation, and should identify outliers to raise for discussion. If students look at a range of examples, they are very likely to find variation; therefore, moves analysis can actually help highlight variation within a genre and show how writers have options to achieve their aims. Students can also be encouraged to use moves analysis to bend or remix a genre and compare the effects (Tardy). Like many pedagogical strategies, moves analysis can be a tool for reproducing, critiquing, and/or transforming hegemonic writing practices.

Activities and Process

While there are many possible ways to conduct a moves analysis in a class setting, we have generally had success using the following process:

First, conduct a moves analysis of a familiar genre.

The student absence email is our go-to genre because student writers have a close understanding of the rhetorical purposes and it brings some levity to the analysis process. By using the examples in this chapter or drawing on real student emails—anonymous, of course—teachers can also show some outliers or ineffective examples that elicit some knowing nods or laughs. Once students identify the genre, a brief discussion of context can elicit an understanding of the social action of this genre. We begin by modeling the process of moves analysis with one sample, helping students label each move with actions. Then, in small groups, we ask students to identify and analyze the moves in additional samples. We remind students that moves can be a sentence, a paragraph, or even just a few words, and we ask students to name them with a verb. In the absence emails, students will often use descriptive phrases like “why absent” or “apology”; it may be necessary to explicitly teach how to convert these descriptions into action-oriented phrases like, “providing reasons for absence” and “apologizing for absence.” In more academic genres, students may fall into generalized terminology like “introduction;” the introduction, however, is usually composed of multiple rhetorical moves (Swales).

After identifying the moves, each small group can share out the moves they identified. It’s okay (and expected) that groups will use different terminology. Then, discuss how these moves facilitate the action of the genre. What are students generally trying to achieve with these absence emails? How do the typical moves (apologizing, providing reasons, expressing gratitude etc.) help to facilitate this goal? This step—discussing why certain moves are used—is essential to helping students see moves as rhetorical rather than simply formal. A critique of the genre’s moves can elicit discussion of writer-audience relationship and the embedded power relations of schooling. (We have also found wedding invitations to be an excellent entry point for moves analysis with opportunity for critique and transformation.)

Next, analyze a less familiar genre.

Follow the same procedures to analyze a target genre. It’s helpful first to discuss the social action of the genre. For more complex genres, like grant proposals or academic articles, it may also help to focus on specific sections. Limiting the analysis to a specific section of a longer genre can both focus the activity and remind students that different sections or parts of a text can serve different rhetorical purposes. Once a set of moves have been identified in group and class discussion, creating a table of obligatory, common, optional, and rare moves can be helpful for guiding students to their choices. Again, be sure to leave time to discuss how the moves facilitate the action of the genre.

Finally, have students draft or revise using their knowledge of rhetorical moves.

If you typically require students to reflect on their writing, you may ask them to discuss the moves they chose to use (or not), and why they made those choices. Christine likes to have students put in-text comments in their final drafts identifying their rhetorical moves and explaining their choices for using them (or putting them in a certain order).

Resources and Samples for Moves Analysis

The Statement of Need excerpts provided in the chapter are from sample grant proposals posted to Candid Learning (https://learning.candid.org), a resource site for nonprofit organizations formerly known as GrantSpace. Candid Learning requires registration, but it is free and has a wealth of resources. The three samples shared in this chapter can be found on the sample proposal page: https://learning.candid.org/resources/sample-documents/?tab=tab-fullproposals. Some of these proposals even include feedback from the funder describing why the proposal is effective.

We have also used the WPA/CompPile bibliographies for annotated bibliographies (https://wac.colostate.edu/comppile/wpa/). The Michigan Corpus of Upper-Level Student Papers (MICUSP) (https://micusp.elicorpora.info/) includes successful student writing in a variety of genres by upper-level undergraduates and graduate students. Former student work can also make for excellent (and varied) samples for moves analysis.

For further discussion on carrying out moves analysis activities, see chapter 2 of Sunny Hyon’s Introducing Genre and English for Specific Purposes and chapter 4 of Christine M. Tardy’s Genre-Based Writing: What Every ESL Teacher Needs to Know.

Discussion Questions

- The authors of this chapter present a brief moves analysis of “student absence emails.” Why do you think these moves have become typical of this genre? If you have written a similar email recently, discuss how or if your moves align with the moves described in the chapter. How might your relationship with your professor affect the moves you use in such an email? What other factors might affect your use of different moves, or even your language choices within those moves? How might the moves in an absence email compare to a “grade change request” or an “appointment request” email to a professor?

- After analyzing student absence emails for moves, write three samples: one that you think is “prototypical” of this genre, one that you think would be poorly received by the instructor, and one that is not standard but would be especially successful. What did you learn from writing these samples? How did your moves analysis inform the choices you made in writing?

- The discussion of the grant proposal Statement of Need suggests that audience awareness is important in deciding which moves may be obligatory and, perhaps, where innovation might be acceptable or even encouraged. What other factors might you consider when determining which moves will be effective in the genre you are writing?

- Think about a time when you felt like you had to bend or transform the conventions of a genre in order to achieve your purpose. How did you make choices about which moves or conventions were necessary to keep, and which could be adapted?

- Gather a few samples of a genre from a discourse community you belong to and conduct a brief moves analysis. What is the action this genre carries out and how do the moves help it achieve that action? What can the common moves tell you about how structure and language create and reflect this community? 6. Some genres tend to be more open to variation than others, including in their use of moves. Make a list of genres that you think are more open to variation and those in which bending the norms may be riskier. What kinds of things might affect your choices as a writer to depart from common moves or other features of a genre?

- This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) and is subject to the Writing Spaces Terms of Use. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/, email info@creativecommons.org, or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA. To view the Writing Spaces Terms of Use, visit http://writingspaces.org/terms-of-use. ↵