17 Read the Room! Navigating Social Contexts and Written Texts

Sarah Seeley; Kelly Xu; and Matthew Chen

Overview

This chapter is a collaboration between a professor (Sarah Seeley) and two former students (Kelly Xu and Matthew Chen).[1] We begin with a discussion of a key concept: the discourse community. In doing so, we illustrate why it is necessary to examine the social side of communication. This is an invitation for readers to think about the fact that academic communication practices are structured in ways that are actually quite similar to the more familiar communication practices they use on a daily basis. We offer readers a framework for understanding how the social assumptions associated with familiar communicative contexts may be useful in understanding new or unfamiliar contexts.

We use the social media platform TikTok as an extended example as we explore the various criteria that define a discourse community. Xu and Chen then offer examples of how people become competent communicators within the context of new new-to-them scientific discourse communities. They cover topics including learning a “hidden” lexicon, building confidence and independence, and navigating tacit power hierarchies. These experiences reinforce the fact that effective communication requires contextual awareness and that understanding social norms is essential for developing that awareness.

Navigating new communicative contexts can be tricky. This is true of enrolling at a new school, starting a new job, or joining a new friend group. In each case, we need to start by “reading the room.” This means identifying the values and circumstances that shape the new social context so we can communicate confidently and appropriately. But, as we know, what it means to speak or write “appropriately” is not the same in all social contexts. While it may seem like a stretch to compare the task of writing a lab report and that of writing a text message, each context equally requires us to examine what counts as “appropriate.” This chapter offers you tools and examples that should help you examine and respond to the social circumstances that characterize unfamiliar contexts in your own life.

To help guide the process of “reading” whatever “room” you may find yourself in, we will begin with a discussion of an important concept: the discourse community. We will use the social media platform TikTok as an example as we explore the various criteria that define a discourse community. We will then move on to offer two narrative-based examples of how college students have navigated the social challenges involved with becoming productive members of new-to-them scientific discourse communities. Kelly Xu will detail her experiences as a biology student interning at a cancer research institution, and Matthew Chen will discuss his experiences of being a mechanical engineering student doing research in an ecology laboratory. We juxtapose these scientific examples with the TikTok example because we want you, the reader, to understand that academic communication practices are structured in ways that are actually quite similar to the more familiar communication practices you use on a daily basis.

The Discourse Community

Being new to “the room” is an inevitable experience. This happens whenever we start a new class or accept a new job. We have to learn the language and expectations required to succeed in the new situation. The discourse community concept will help you examine, understand, and thus succeed in those new situations. The linguist John Swales first developed a list of criteria for defining discourse communities in his book Genre Analysis (1990). In a more recent (2017) article, he revised these criteria because he wanted to account for the changing nature of communication in our contemporary world. In the following list, we are paraphrasing an article published in the journal Composition Forum, where Swales suggests that discourse communities are defined by the following eight criteria:

- broadly agreed upon sets of goals

- ways of communicating within the group

- member participation that provides information, feedback, and initiates action

- the use of specific formats (genres) for communicating within the group

- the use of specific vocabulary (lexis) for communicating within the group

- a core group of experienced members

- the sense that certain things can be left unsaid

- horizons of expectation

In the next section, we will have a closer look at each of these criteria.

How Can These Criteria be Used to Understand TikTok?

At the time of this writing, TikTok is consistently in the news for its role in circulating conspiracy theories and cultivating extremism (Ovide; Clayton). The community is receiving increasing amounts of attention, and, with the mobile app having been downloaded more than 2 billion times, it offers a timely case study: can TikTok “tick” all the boxes in Swales’ list (Brown; Leskin)?

First, Swales suggests that a discourse community is defined by a broadly agreed upon set of goals. Can we say this is true of the TikTok community as a whole? Probably not. Like most others of its kind, this platform is made up of distinctive interest communities (more on this in a moment). Such divisions make it hard to say that the community is defined by shared goals. For example, it is difficult to claim that the dancer Charli D’Amelio shares the same goals as the people behind the far-right extremist accounts. It is similarly difficult to claim that #CottageCore creators like @speckledhijabi or users posting to #BlackLivesMatter share the same goals as content creators who are cancelled for their use of racist slurs (Jennings). Within this vast social landscape, the only agreed upon goals are very, very broad: producing, circulating, and accessing new and quickly consumable content. As we know, that could mean nearly anything.

What about ways of communicating and participating within the community? Here is where we move onto firmer ground. All social media platforms offer methods for group communication and participation. From rotating trends to “likes” and hashtags, TikTok seems to tick boxes two and three on Swales’ list.

How about specific formats and vocabulary? Tick, tick. TikTok is defined by short video content sharing. Creators can loop or otherwise string together shorter clips to circulate “larger” videos that are up to 60 seconds long. In this way, TikTok builds on the short video format, or genre, that was a staple of its predecessor Musical.ly. Of course, this genre has also been popularized by Vine’s 6 second videos (R.I.P.), and we can also see short form video content sharing in other places, like 15-second Instagram Reels.

Now, does TikTok have a core group of experienced members? Well, yes and no. We cannot answer this question without circling back to our discussion of the first criterion. Recall, we had trouble saying that the TikTok community, as a whole, shares any specific goals. Building on this, we can say that there are experienced or core members, but that they are clustered across different “pockets” of the community. These clusters can be mapped across one important divide: Alt TikTok vs. Straight TikTok. Within these very large categories, content is characterized by wildly different goals and values. So, while there are core members within “sub-communities” across, for example, Alt TikTok, individual users also retain the freedom to shape genres and vocabulary in individualistic and grassroots ways (Sung).

Swales’s seventh criterion relates to the fact that, within a given community, certain things can be left unsaid. Drawing on the work of the linguist Alton Becker, Swales calls this “silential relations.” To understand this concept, we could think about the building abbreviations and program acronyms that are used on our respective campuses. For example, as members of our own campus-based discourse community, we, the writers, know exactly what “COMM+D” means, so we don’t need to spell out the Center for Global Communication and Design. We’re sure there are similar acronyms and abbreviations that define your campus community. We could also think about “silential relations” in terms of slang. From platform-wide slang like “story time” and “duet” to the slang that characterizes TikTok’s niche communities, this box is ticked.

The final criterion relates to something Swales calls a “horizon of expectation.” As he puts it, a discourse community “develops horizons of expectation, defined rhythms of activity, a sense of its history, and value systems for what is good and less good work” (Swales, “Concept”). There are a lot of considerations bundled here. Linking back to the idea that TikTok users generally aim to produce, circulate, and access new and quickly consumable content, we can see, once again, that the TikTok community as a whole is too large to be meaningfully examined in terms of some of these criteria. Numerous histories, value systems, and associated social expectations are observable across TikTok at any given moment. For example, at the time of this writing, the TikTok site indicates that videos categorized under #BLM have received a collective 12.3 billion views. On the other hand, TikTok also had to issue an apology in June 2020 over allegations of censoring this very hashtag (Harris). In other words, TikTok is comprised of a myriad of “rooms” that may need to be “read” quite differently.

As a new(ish) member of a university community, you may be interested to know that, like TikTok, the academic community as a whole is also too large to be meaningfully examined as a singular discourse community. What counts as “good” writing or “successful” communication is going to vary widely across the classes you take in different disciplines. This is because disciplinary goals, genres, languages, and expectations all vary. We must always read the room and respond accordingly. Now that we’ve explored how the discourse community criteria can (and cannot) help us understand TikTok, Kelly Xu and Matthew Chen will apply the same ideas in their stories of learning social norms and gaining authority as new members of scientific discourse communities.

The Lab Experience: Free Trial vs. Full Membership (Kelly)

After interning at a medical oncology lab for two summers, I have experienced being a member, an outsider, and everything in between. In what follows, I will reflect on these experiences using the discourse community framework. As you likely know from your own experiences, the conceptual boundaries of any community are most evident to anyone who is new. Simply not understanding the tacit rules, structure, and lexis of a community can make one feel ostracized as an outsider to the “in group.” In the case I’m about to describe, I entered the lab community as an intern who had minor publications and one year of undergraduate education under my belt. I was certainly under-qualified, and I felt daunted before I even stepped foot in the lab.

In lab settings, educational qualifications underlie all power structures. In other settings, positions may be malleable and accommodating based on pertinent experience, but in the lab, power is clearly defined by education and publication status. The Principal Investigator holds the most authority, followed by MD/PhDs and post-doctoral students, then doctoral students, followed by lab technicians, and finally undergraduate interns. We will also see how this same type of hierarchy structures other lab contexts in the next section, but for now, we should keep in mind: no amount of seniority as an undergraduate can ever allow for a “promotion” to the level of a PI.

Upon receiving my internship offer, I felt like I was infiltrating the company, rather than earning my position. Although I owned a company ID and looked like any other lab member, there were clearly invisible borders that I needed to breach to become an integrated member of the community. I was a long way from understanding the means of participating and communicating that were seemingly obvious to core members of the community. For example, even menial tasks like picking up mice revealed the fact that I was still an outsider. My mentor often said that mice perceive their handler’s emotions and react correspondingly. While she confidently grabbed the base of their tails with ease and they would immediately stop squirming, my hesitant grip allowed the mice to wriggle out with ease.

Lab-specific lexis, or vocabulary, also proved to have a learning curve. I was fascinated by the secret language of abbreviations and terminology that researchers commanded so fluently. I took fastidious notes on the aliases we used for reagents, the tiny modifications made to procedures, etc. But I found that even self-proclaimed mastery of the genres and lexis of this community were insufficient for me to establish a place in the lab. Though I rehearsed the words I heard my colleagues use so expertly, they felt ill-fitting and improper when I used them in practice, akin to a child wearing an oversized suit. More precisely, I didn’t (yet) feel I had the right to use such mature terminology because I still had so little experience. I now realize that the attribute I lacked and yearned for so distinctly was authority. Since gaining authority is a multi-faceted task, I want to discuss two components of this process: autonomy and reputation.

Autonomy

From where I sit now, I see my first summer interning as a “training period” wherein I lacked the agency to plan my own schedule or act without supervision. To put it in Swales’ terms, I could not yet participate independently or initiate my own action. While my days were rigidly structured and scheduled by my mentor, I looked upon the independence of my lab peers with admiration. They were so familiar with the intervals of time they needed to complete aspects of their projects that they could come into work at any time and leave at their leisure. Whereas I was paid hourly and expected to work 9-5, their jobs seem so much more integrated into their lifestyles and tailored to their personal work ethic. Perhaps more importantly, they were confident enough in their skills to complete tasks within a time window they allotted themselves. Circling back to Swales’ criteria, it is clear that my peers were self-sufficient enough that they were able to recognize and participate in the rhythms of work that support overarching lab goals. Meanwhile, I was given a generous margin of error in everything I did, from booking lab machines times to pipetting reagents from a mastermix. I had to gain my own footing and learn to function as an individual before I could participate as a member of the community and contribute towards its goals.

For an undergraduate with little formal lab training, there is only so much autonomy you can attain since most procedures must be learned under supervision. However, I would like to argue that I did make some progress towards attaining autonomy. At first, I repeatedly executed the same protocol under strict observation. After verifying that I could successfully replicate one protocol, I was invited to apply the same skills (e.g. pipetting or making a gel) to other protocols without supervision. I repeated this process until I was gradually trusted to learn new protocols entirely on my own. Though I still felt restricted by the structure of the lab hierarchy, I came to appreciate these small landmarks of independence as they reminded me of the progress I was making. The better I understood the goals, actions, and lexis of the community, the more my autonomy increased. Hence, personal growth and increased familiarity are the keys to establishing an autonomous position within any discourse community. Whereas my earliest days in the lab felt like a stressful lab practical, I felt like a valuable partner by the end.

Reputation

I was often scared of asking questions during the first year of my internship. Not only did I lack the confidence to ask a question, but I lacked the basic understanding needed to even form a question. At meetings, I would often stay quiet. This was out of fear that I would ask about something that had already been clearly explained or that I had misinterpreted a figure. Even during my second year, after having completed two rigorous 4000-level biology courses, I still found it challenging to interpret the specifics of my colleagues’ experiments. This, of course, was because I was still developing an understanding of my colleagues’ goals, and I was still in the process of mastering their genres. During the typical lab day, I felt like a nuisance asking what I thought were overly simplistic questions. In fact, I would ask questions in a “bottom-up” manner. I started with asking my undergraduate peers and then worked my way up the ladder if needed because I didn’t want to damage my reputation by annoying the higher-ups. In doing so, I was actually internalizing and taking action within the social structure of the lab.

This social work eventually started to pay off. Another lab member actually consulted me for advice on executing an assay that I commonly performed. I was shocked and honored. This was a recognition of my proficiency and knowledge, and I was elated that, despite my position in the academic hierarchy, my work and reputation preceded me. I had established my colleague’s respect, which went a long way toward making me feel like I was establishing my own authority. Afterwards, I proudly listed “PCR” as a lab skill on my resume; I finally felt confident enough in my technique to claim that I specialized in it. I no longer felt like I was a child donning an ill-fitting lab coat, but began to believe in my own credibility. Thus, practice with the genres and lexis of the lab allowed me to gain confidence as a researcher.

Finally, I took the ultimate test of trust and reputation: the dreaded lab meeting. Lab meetings are notoriously difficult because one is required to present their research progress to-date. In addition, rigorous follow-up questions test your knowledge of every detail of your project and (potentially) highlight every oversight. For example, it was insufficient for me to just know the names of the cell lines I was growing. I also needed to know why they were chosen and be able to discuss the levels of expression for multiple genes in each. To put it in Swales’ terms, the lab meeting is a demonstration of member participation: you provide information, receive feedback, and action is initiated. Though it was incredibly daunting, I was proud to work with my mentor to create the slides I would present as well as field questions from the audience. By being held to the same scrutiny and high standards as my peers, I really felt like I was no longer just an undergraduate intern but recognized as a true researcher.

One of the most important ways to gain membership within a new discourse community is to cultivate your confidence and a sense of belonging. While this involves rather gradual changes in perception, it is something we can all take control of as individual communicators. Ultimately, though, becoming integrated into a discourse community is a more nuanced process than a simple list of criteria might indicate. Learning vocabulary and techniques is merely the beginning of fitting into a discourse community. This is true in the same way that reading a book can’t replace having the actual experience being described. However, the novice communicator can make the integration process less daunting by setting more attainable goals. We can proudly reflect on the landmarks we achieve. In my case, this meant presenting with my mentor during a lab meeting or pausing to feel gratified after a peer had asked me for advice. Upon concluding my two-year internship, I finally felt like I earned a place in my lab community. I have moved beyond the free trial into the highest level of membership I can afford for now.

From Robots to Frog Guts: An Engineer in Ecologist’s Clothes (Matthew)

Going into my second semester of college, I found myself wanting to do something apart from my regimented engineering classes, so I decided to join an ecology lab. My routine of experimenting with circuits and fixing up machines was no more. Instead, I was experimenting with snails and fixing lunch for frogs. Some may ask why I would do this. Through countless hours spent hiking, mountain biking, and camping, the environment has become significant to me. That said, I quickly realized the vast difference between my personal environmental interests and the ecological knowledge these researchers possessed. Similar to the situation described in the previous section, I had some work to do! In order to establish myself within this discourse community, I had to accomplish three main tasks: adapting to their way of communicating, understanding their professional motives, and building their trust. Progressively meeting these goals allowed me to integrate myself into the ecology community in increasingly meaningful ways.

Throughout that first semester, I picked dead invertebrates from a slushy mixture of dirt and sand for eight hours a week. As we saw in the previous section, mundane tasks often serve as a foundation for adjusting to new environments. After weeks spent alone in a windowless lab, churning through one Petri dish of smudge after another, a post-doc invited me to their weekly “journal discussions.” I accepted the invitation immediately and found out later that these meetings were a venue for discussing ecology and environmental science papers.

Going into my first journal meeting, I felt that my contributions were going to be pointless. At first, this fear was confirmed. While the graduate students and postdocs shared their thoughts, I was frantically Googling on my laptop in an attempt to understand them. Though I had read the entire paper front to back, I hadn’t grasped the context behind it. These ecologists came to these discussions with years of experience conducting, writing up, and publishing experiments. Thinking in terms of Swales’ criteria, these years of experience furnished them with a context for understanding the goals of ecological research, for critiquing such research, for decoding ecology genres, and for using ecology vocabulary. I had had none of that.

However, after attending a few of the discussions, I started to understand more. For example, I realized that no one says “standard artificial media 5-salt culture water.” This phrase is ridiculously long and thus shortened to SAM-5S water. Here, we can see the concept of silential relations at play, yet understanding what should be said and what can remain unsaid required more than just learning word definitions. It also required me to understand the ideas within a larger context. For example, through talking with a grad student, I learned the context surrounding the issue of pseudoreplication, which is a situation where one would artificially inflate their sample size by sampling multiple times from a single source. She explained how she would avoid this by setting up 50 individual pools of water with the experimental chemicals and animals. Thus, the experiment would generate true statistical significance, which would make it publishable, thus serving one of the main goals of this discourse community.

In addition, I realized that the journal discussions were always guided by a series of standard questions. Where and when was the paper published? What is the significance of the results? Do they make sense? Are there any discrepancies? Recognizing the format of the discussions and learning more about ecology and scientific genres, I was able to understand the goals of the lab and the context behind their experiments. After attending several journal discussions, I became comfortable speaking my thoughts to the group. I began relating the paper we were discussing to the current research being done in the lab, and making these connections allowed me to get a deeper understanding of the life of an ecologist. Doing this, my comments and questions began sparking a more in-depth discussion, rather than a dead-end conversation. I no longer needed to stress about what to say next or worry about the discussion becoming awkward. Thinking in Swales’ terms, this is when I started to internalize one facet of the community’s horizon of expectations: the value system that defines meaningful (and not-so-meaningful) commentary and critique.

On another occasion, a postdoc started passionately exclaiming how the figures in a paper were way too confusing and complex. This showed me how undoubtedly passionate they are about their work, and how they meticulously critique the textual artifacts that make up their scientific community. It was also relieving to know how even the most experienced in the lab sometimes found figures difficult to interpret too, with the difference being that they are able to back up their critiques with an onslaught of evidence. With each passing journal discussion, I was increasingly able to relate to the ecologists’ work and get to know them better. This is how I started to break free of that “new person” feeling.

While these journal discussions expanded my knowledge of ecology, I also gained insight into how the scientific research community communicates and circulates information. Put differently, these are the actions encompassed by Swales’ second and third criteria. As opposed to engineering, the scientific method for demonstrating results is quite textual. This differs from the more physical nature of engineering, as while I am resizing the fit of a 3D model, the ecologists are meticulously rewriting their manuscripts so as to appease reviewer two. In noting this realization about textual vs. material communication, we can circle back to Swales’ first and fourth criteria. Here we see members of engineering and ecology discourse communities using very different research genres, or formats, to achieve very different goals. And, to put it in more day-to-day terms, I learned that emailing busy ecologists is a nuanced task. These messages had to be short and to the point if I wanted to receive a response in the same week!

At the end of the fall semester working in the lab, I’d learned how these ecologists communicate, how they characterize their passions and goals, and how I fit into the community. These successes paved the way for my next opportunity: a summer internship position. Shifting into the new role, I would continue the work of picking dead invertebrates out of wet dirt. Then, after three weeks, a grad student asked me if I wanted to catch snails from a pond. I was so excited to finally work with an organism that was alive. A little slow, but alive, nonetheless. I picked each snail out from the pond so gently, like they were the last one on earth, and I brought them back to the lab for the graduate student. Upon examining the snails and realizing they were all alive, she told me “good job.” This very brief interaction demonstrated that she regarded snail collection as the most basic of tasks, while I perceived it to be more involved and sophisticated. Essentially, I was the ecologists’ coffee boy, but instead of delivering coffee, I delivered snails!

Nevertheless, after having success with retrieving snails, I was able to communicate to my co-workers that I am capable of successfully carrying out more complex tasks. After around two weeks of snail work, I advanced to a more complex (and quicker!) organism: frogs. I began transporting live (jumping!) frogs from outdoor experiments into the lab. Given the strong possibility that I might lose a frog, or a data point in the eyes of a PhD student, I worked alongside another person. After a week as a member of the frog-catching duo, I was told I could catch them on my own. I was no longer the undergrad who picks dead worms from dirt. I had become the undergrad who catches live frogs out of kiddie pools!

In addition, I started to realize subtleties in the way my colleagues worked, and I developed my own daily routines. I was finally gaining some of that autonomy Kelly Xu discusses in the previous section. For example, each morning I would organize the glassware, check-up on the live animals, collect specific animals, and touch base with the director. At the close of each day, I would start washing glassware and check our chemical inventory. Initially, I did not do any of those things; it was only after talking to them over lunch each day that I came to recognize my colleagues’ workloads and time constraints. So, when I was given a menial task like washing dishes, I worked it into my routine and continued to do it each day, thus freeing up crucial time for my colleagues. By demonstrating that I shared the ecologists’ goals and viewpoints, I was able to gain their trust and integrate myself into their discourse community.

Conclusion

Regardless of the discourse community, gaining membership and authority involves recognizing the social context that surrounds communication. It demands that we read the room. In doing so, we can gain trust through demonstrating our awareness of a community’s goals, genres, and language. As we have seen through our explorations of social media and scientific discourse communities, understanding situated social norms is essential for developing that awareness. Effective communication always requires contextual awareness. This is the social side of communication. In order to understand and be understood, one must learn to read the room. We hope that our examples and discussions have illustrated the intellectual and emotional components of being a novice communicator. Further, we hope you now have the tools to embrace this novice status. It is inevitable that we will all wander into a new room from time to time. Once we cross a new threshold, it is up to us to find knowledge and power there.

Works Cited

Barbaro, Michael. “Cancel Culture, Part 1: Where It Came From.” The Daily, The New York Times, 10 Aug. 2020. The New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/10/podcasts/the-daily/cancel-culture.html. Accessed 10 Aug. 2020.

Becker, Alton L. Beyond Translation: Essays Toward a Modern Philology. University of Michigan Press, 1995.

Brown, Dalvin. “Survey Finds More Than Half of All Americans Back Potential Ban on TikTok.” USA Today, 12 Aug. 2020, https://www.usatoday.com/story/tech/2020/08/12/harris-poll-survey-americans-tiktok-ban/3353051001/. Accessed 12 Aug. 2020.

Clayton, James. “TikTok’s Boogaloo Extremism Problem.” BBC News, 2 July 2020, https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-53269361. Accessed 9 Aug. 2020.

Geertz, Clifford. Local Knowledge: Further Essays in Interpretive Anthropology. Basic Books, 1983.

Gumperz, John J. “The Speech Community.” International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, edited by David L. Sills and Robert K. Merton, Macmillan, 1968, pp. 381-86.

—. Language in Social Groups. Stanford University Press, 1971. Harris, Margot.

“TikTok Apologized for the Glitch Affecting the ‘Black Lives Matter’ Hashtag After Accusations of Censorship: ‘We Know This Came at a Painful Time.’” Insider, 1 June 2020, https://www.insider.com/tiktok-apologizes-for-blm-hashtag-glitch-after-censorship-allegations-2020-6. Accessed 6 Aug. 2020.

Jennings, Rebecca. “This Week in TikTok: The Racism Scandal Among the App’s Top Creators.” Vox, 28 April 2020, https://www.vox.com/the-goods/2020/4/28/21239065/emmuhlu-n-word-mattia-polibio-chase-hudson-tiktok. Accessed 6 Aug. 2020.

Johns, Ann M. “Discourse Communities and Communities of Practice: Membership, Conflict, and Diversity.” Text, Role, and Context: Developing Academic Literacies, Cambridge University Press, 1997, pp. 51-70.

Leskin, Paige. “TikTok Surpasses 2 Billion Downloads and Sets a Record for App Installs in a Single Quarter.” Business Insider, 30 April 2020, https://www.businessinsider.com/tiktok-app-2-billion-downloads-record-setting-q1-sensor-tower-2020-4. Accessed 9 Aug. 2020.

Luu, Chi. “Cancel Culture is Chaotic Good.” JSTOR Daily, 18 Dec. 2019, https://daily.jstor.org/cancel-culture-is-chaotic-good/. Accessed 10 Aug. 2020.

Ovide, Shira. “A TikTok Twist on ‘PizzaGate.’” The New York Times, 29 June 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/29/technology/pizzagate-tiktok.html. Accessed 9 Aug. 2020.

Rectenwald, Michael and Lisa Carl. Academic Writing, Real World Topics. Broadview Press, 2015.

Sung, Morgan. “The Stark Divide Between ‘Straight TikTok’ and ‘Alt TikTok.’” Mashable, 21 June 2020, https://mashable.com/article/alt-tiktok-straight-tiktok-queer-punk/. Accessed 9 Aug. 2020.

Swales, John M. Genre Analysis: English in Academic and Research Settings. Cambridge University Press, 1990.

—. “The Concept of Discourse Community: Some Recent Personal History.” Composition Forum, vol. 37, 2017, https://compositionforum.com/issue/37/swales-retrospective.php.

Teacher Resources for Read the Room! Navigating Social Contexts and Written Texts

Overview and Teaching Strategies

John Swales’s discourse community framework has been widely anthologized. It is, of course, something he has updated over time (Genre; “Concept”). It also builds on prior work in linguistic anthropology (Gumperz “Speech”; Language), and it is often understood as being adjacent or complementary to other frameworks relating to the social nature of communication (Geertz; Johns). We raise these points because they offer a good context for how one might teach this chapter in a way that makes the discourse community concept plausible for students who are new(ish) members of academic discourse communities. Learning to read the room is only truly helpful if one can also understand a broader lay of the land, so to speak.

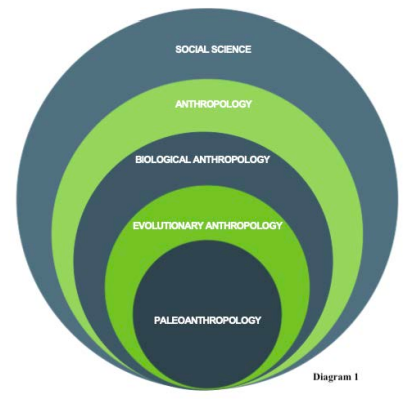

Scholars (in any discipline) develop ideas that retain varying amounts of power and authority over time. They do this within their discourse communities. Because this is an academic context, it means they do so within disciplines and sub-disciplines, which are “rooms” of differing sizes that students may need to learn how to “read.” For example, we could visualize disciplinary relationships as a series of nesting circles. The largest category in figure 1, social science, encompasses many distinct disciplines: anthropology, sociology, political science, etc. The diagram further maps out one tiny corner of the anthropological knowledge-making terrain. What’s more, we could have just as easily selected the biological sciences or the humanities and displayed a similarly small slice of disciplinary relationships within, for example, ecology or media studies.

Our overarching point is this: the smallest subset of academic inquiry pictured within our diagram—paleoanthropology—is a discourse community. It may share features with the larger social science or anthropology discourse communities, but we can still expect that it will have its own unique features. Paleoanthropology is, in effect, its own room, and ought to be read as such. Yet, one can still learn to understand it by applying what they know from inhabiting other rooms: adjacent academic disciplines and subdisciplines, or different workplace or media communities. Similarly, the TikTok section of our chapter offers a pop cultural framework for illustrating how far Swales’ criteria can (and cannot) stretch as we attempt to read a room. We believe this social media discussion can productively set the stage for parallel in-class discussions about academic knowledge production and the boundaries of academic discourse communities.

Tracing the history of an idea—when it appeared, where, and how it’s been used or expanded—is only possible when we can map out these kinds of disciplinary relationships. The powerful ideas tend to be cited, developed, and expanded on by other scholars within and across disciplinary discourse communities. The migration of Swales’ framework out of linguistics and into writing studies is a good example. In order to truly understand an idea, students must go outside of the content to examine the context of its production. These are very important skills. This is especially true for speakers and writers—like your students—who are in the process of becoming members of new academic discourse communities. As we illustrate in our chapter, this novice status is an inevitable social condition.

This chapter may be assigned during a unit focused on discourse communities, but it also presents ideas and prompts discussion that may be productive for transitioning into a unit on conducting academic research and narrowing research questions. In support of these goals, we offer two class activities. The first is specifically focused on helping students develop their understanding of the discourse community concept. The second is more a method for integrating oneself into an academic discourse community— particularly those associated with the humanities and social sciences.

Activities

Discourse Communities and Power Struggles: Examining Cancel Culture

This first activity was created for use during class time, so the podcast (audio and transcript options linked below) should be assigned in advance. At that point, class time could be loosely structured in “think, pair, share” terms.

As we know, there are core members within social media “subcommunities,” but individual users also retain the freedom to shape genres and vocabulary in individualistic and grassroots ways. This freedom can be seen across social media outlets, for example: upvoting on Reddit or the general phenomenon of cancel culture.

Today, we will examine cancel culture. The rise of this phenomenon draws attention to an important question on the social media discourse community landscape: How is power distributed? How are people scrambling to redistribute it? What are the implications of our own participation in these power structures?

You listened to (or read) an episode of The Daily called “Cancel Culture, Part 1: Where It Came From” (Barbaro). In it, host Michael Barbaro explores what it means to be canceled and how the whole thing began. Take five minutes to recall the episode, review any notes you made, or skim the transcript. Once you’re up to speed, we will form groups and engage with the discussion questions outlined below. I’ll pop in to hear some of your ideas individually, but you should regard the small group discussion as a platform for contributing to a full class discussion when we come back together toward the end of class.

Discussion Questions

Please begin by reading all the questions that follow. Decide whether you’d like to focus your discussion on Cluster 1 or Cluster 2. Once you make that choice, you should be thinking in discourse community terms. In other words, how might the discourse community concept help us to wade through this messiness and create situational answers to these questions? For example, what can genre and vocabulary tell us about any of these definitions or applications of cancel culture? Are terms like “liberal” or “young person” narrow enough for analyzing cancel culture? Are all “young people” members of the same discourse communities? Recall Swales’ concept of silential relations. How does a sense that certain things can be left unsaid support (or thwart) the politicization or weaponization of cancel culture?

Cluster 1

Barbaro presents speech snippets where both Barack Obama and Donald Trump discuss cancel culture. How can cancel culture be labeled as “bad” in two ways that are so very different? Is “canceling” to be avoided because it’s impolite or some kind of cop-out as Obama seems to suggest? Is it to be criticized because the “liberals” are weaponizing it, as Trump suggests? Is it even possible to analyze this phenomenon apolitically?

Cluster 2

All types of people exhibit socially unacceptable behavior, whether they are relatively powerful or relatively powerless. Given this, how can we make a distinction between canceling a celebrity and canceling an “average” citizen? How should personal security and loss of income factor into this distinction? Should we even draw a line here? Where does it seem to be drawn currently? In whose minds? Should it be re-drawn?

The Synthesis Grid

The Synthesis Grid activity, as adapted from Rectenwald and Carl, may be enacted during class or used as a formal assignment. It can be productive to assign students to submit a synthesis grid as a supporting document that accompanies, for example, a discourse community analysis, a genre analysis, or a researched argument.

What Is Synthesis?

Synthesis is an important writing practice. It is an especially important rhetorical strategy for learning to write in academic contexts. When writers offer a synthesis, they are combining, blending, or weaving related ideas from different sources.

What Is the Value of a Synthesis Grid?

Producing a synthesis grid offers you an opportunity to take notes in a structured way so you deepen your understanding of a particular topic or question. In effect, a synthesis grid is a material artifact of your research process. It is a record of all the reading and thinking you’ve done as a part of your writing process. Since writing can’t proceed without reading and thinking, it can feel particularly satisfying to document all this “behind the scenes” work. Then, you want to apply that “behind the scenes” work in your writing. For example, offering a synthesis within an academic argument is a very common (and effective!) method for establishing credibility.

How Do You Create a Synthesis Grid?

- You want to begin by settling on a particular topic or concept that will be the subject of your grid. For example, perhaps you want to write about cancel culture. This is a complex and controversial phenomenon with its own history, so starting a synthesis grid may help you to solidify your own ideas on the subject.

- Once you have your topic, you need to locate three or four pieces of writing that deal with the topic. Keeping with the cancel cultruel example, I might decide to start with a podcast transcript—Barbaro—and an article—Luu—then build my grid from there.

- Once you have the topic and some reading material, you want to create the “shell” of the grid. This involves making a series of rows that correspond to the number of readings you want to include. This also involves making a series of columns that correspond to the sub-topics you are interest in learning more about. See table 1 for an example.

| Writers | Sub-topics ✓ | ||

| Redistributing Power | Politicization | Topic TBA | |

| Michael Barbaro | |||

| Chi Luu | |||

| Writer TBA | |||

- Once you’ve created the shell, you want to continuously add your notes as you move through readings related to your topic. Keep in mind that you won’t know all the sub-topics when you begin this activity. You will fill them in as you learn more. For example, perhaps you were interested in the redistribution of power ot start with, theyn you noticed that writers were often discussing the politicization of cancel culture. That’s a good indicator that you might want to add a column for politicization. Perhaps you then realize many writers are discussing the history of the phenomenom or how the pandemic has shaped the phenomenon. Perhaps you notice many writers discussing a specific social implication—for example, the negativity or destructiveness that is often attributed to cancel culture. If so, you should similarly follow such cues to add additional columns to your grid.

How Do You Use a Synthesis Grid?

Recall, the value of the grid is two-fold. It allows you to document the “backstage” work of reading and thinking, and it assists you in pulling the ideas you developed into the “foreground.” What follows is a sample synthesis that could be derived from this grid (even in though it’s still a work in progress). We can see how the ideas presented by Barbaro and Luu might be woven together to set up a line of inquiry in Table 2.

A Sample Synthesis

While cancel culture may appear to be a relatively new phenomenon, people have long been mobilizing against perceived injustice both on and offline. Both Michael Barbaro and Chi Luu have recently discussed this phenomenon and how it relates to internet language and culture at large. Barbaro and Luu each present the perceived positives and negatives surrounding cancel culture. Barbaro’s podcast episode was released more than six months after Luu’s article was published, and it draws on the words and experiences of politicians, celebrities, and everyday racists as a method for exploring the complexities of this phenomenon. One major question within all of this is how to differentiate between the “cancelation” of a relatively powerful person versus that of a relatively powerless person.

Connecting the Synthesis Grid to the Discourse Community Concept

As we suggest in our chapter, learning to mobilize the discourse community concept is an important method for “reading the room.” Learning how, for example, vocabulary or genre is shaped by social expectations sets student-writers up to understand writing as an audience-driven act. And, learning to map the epistemological landscape of a social debate similarly sets student-writers up to understand academic writing in terms of situated social exigencies.

| Writers | Sub-topics→ | |

| Redistributing Power | Politicization | |

| Barbaro | Barbaro begins by laying out the opposing viewpoints that often characterize cancel culture. On one hand, it is viewed as: “a growing phenomenon of public call-outs that, for some, are a necessary way of demanding accountability from public figures and those in power.”

On the other hand, some view the phenomenon as a series of “mob attacks in which a specific point of view is imposed on everyone, even those with little power, through rising intolerance and public shaming.” Barbaro explores a number of cases. On the celebrity end, Kanye West, Alison Roman, and J.K. Rowling are discussed. On the “average citizen” side of things, the Central Park incident involving Chris Cooper and Amy Cooper is discussed. It’s important to make a distinction between “mobbing” a powerful celebrity to make them accountable and doxing or firing an “average” (albeit racist, sexist, homophobic, etc.) citizen. But if there is a line to be drawn, where is it currently drawn? In whose minds? Should it be re-drawn? |

Barbaro links audio of President Obama from 2019: “I do get a sense sometimes now, among certain young people — and this is accelerated by social media — there is this sense sometimes [that people think] the way of… making change is to be as judgmental as possible about other people. I can sit back and feel pretty good about myself, because man, you see how woke I was? I called you out.”

Barbaro later links audio from Donald Trump’s speech at Mt. Rushmore on July 4, 2020: “One of their political weapons is cancel culture: Driving people from their jobs, shaming dissenters, and demanding total submission from anyone who disagrees. This is the very definition of totalitarianism. And it is completely alien to our culture and to our values. And it has absolutely no place in the United States of America.” How can cancel culture be labeled as “bad” in two ways that are so very different? Is “canceling” to be avoided because it’s impolite or some kind of copout as Obama seems to suggest? Is it to be criticized because the “liberals” are weaponizing it, as Trump suggests? Is it even possible to analyze this phenomenon apolitically? |

| Luu | Chi Luu discusses how internet language draws attention to how people are less socially passive (if they ever really were). She writes, “these terms [#MeToo, woke] seek to open up to debate the things that were once blindly accepted and taken for granted.” She further notes that some people are very much afraid of how the internet has given voice to “random bunch[es] of people who have banded together in some common cause. When this common cause is being aggrieved against someone’s problematic behavior, and results in ‘calling out,’ silencing or boycotting the problematic behavior, we now call this ‘cancelling’ someone.”

As she points out, there is power in these call outs, which “can spontaneously self-assemble a community based on #shared beliefs where there may not have been one before, tapping into a power that members of a group individually may never have had.” |

Luu mentions how Barack Obama called upon young people to avoid being overly judgmental online. And, as Luu notes, Obama’s comments are a, perhaps unsurprising, instance of someone in power reacting negatively to “power being wielded by [those who] are relatively powerless.”

Luu suggests that, “though we tend to focus on the negative of cancelling, we forget that there may be a good side—not just praise or approval, but the fact that injustices that were once allowed to thrive can now be revealed and acted upon by a group.” |

- This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) and is subject to the Writing Spaces Terms of Use. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/, email info@creativecommons.org, or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA. To view the Writing Spaces Terms of Use, visit http://writingspaces.org/terms-of-use. ↵