6 Claimsmakers and their Audiences

Learning Objectives

In this chapter you will:

- Compare and contrast activist and expert claimsmaking.

- Apply social movements theory to the anti-fracking movement.

Perhaps you’ve realized by now that the process of making claims about social problems is an inherent part of the work involved in launching social movements. Social movements were of great interest to me when I was a sociology student because they have historically been a driving force of social change. I made a whole dissertation project out of studying dynamics between activists opposing and supporting “fracking” – a method of oil and gas extraction introduced in the U.S. circa 2007. That makes me something of a social movements nerd. It also makes me quite a bit skeptical of activists! My research in the Southern Illinois community led me to see fracking from several different viewpoints and I realized that there are ethically complicated dynamics at play in any movement cause.

In this chapter, we’ll start by looking at a few key terms about social movements, particularly focusing on distinctions between major categories of claimsmakers and the audiences they hope to mobilize. I’ll then review some examples, drawing from my research on fractivists. The hoopla around fracking has simmered out in the last decade as the predictions that it would bring widespread ecological catastrophe largely did not come to pass. But in the fracking story there are relevant parallels to other contemporary movements that are worth reflecting on. Here I’ll be focusing on the environmental movement, fractivism, and a pro-oil counter-movement, but consider how this story applies to other cases.

From Social Problems to Social Movements

As we’ve already explored, one of the central goals of claimsmaking activity is to inspire people to care about and take action to improve troubling conditions. Scholarship about social problems therefore dovetails with scholarship on social movements. David Meyer is a social movements master scholar who offers this definition of a social movement: “Social movements are collective, sustained efforts to challenge existing or potential laws, policies, norms, or authority making use of extrainstitutional as well as institutional political tactics” (Meyer 2015: 12). That’s a mouthful, so let’s break it down.

To say that social movements are collective means that a social movement consists of a group of people. A social movement is not just a single person on a crusade, like Carol Baskin and her collection of exotic cats. Rather, an issue becomes a movement when it mobilizes many people to join in solidarity around a shared cause.

Additionally, social movements are sustained, meaning that they continue for a significant period of time. People may get mad about something, like inadequate local trash service or poorly maintained park equipment, and demand that their local township board or city council fix the problem. But these short-lived efforts don’t rise to the level of a social movement. A social movement is an enduring campaign for change.

Finally, a social movement challenges the status quo. That is to say that social movements dispute, contest, or object to the usual way of doing things. This challenge may use one of two types of tactics, or political activities, to pressure authorities to make changes.

Institutional tactics are political activities that conform to existing, government-approved venues for airing grievances. Examples include testifying at a public hearing, submitting a public comment, launching a letter-writing campaign, or signing a petition.

Extrainstitutional tactics are political activities that fall outside of these approved channels for expressing dissent. Protesting, marching, or engaging in sabotage are all examples of extrainstitutional movement tactics.

In order for an activists’ cause to become a social movement, three conditions must come together (McAdam 1982; Meyer 2015).

- First, activists must bring other people’s view of a troubling situation into alignment with their own and compel action. Frame alignment is like claimsmaking, wherein activists seek to talk about troubling conditions in a manner that inspires sympathy and support.

- Second, conditions in the broader society must be favorable for a given cause to gain traction at a particular moment in time. This is referred to as a political or cultural opportunity for mobilization.

- Third, activists must succeed in mobilizing resources necessary for fueling social movements. These could be human resources, like members, leaders, and experts; material resources, like money and meeting space; cultural resources, like social ties or experience; and organizational resources, such as existing community groups and organizational communication networks.

Activists, Experts, and Expert Activists

Activists are people who take action to remediate a perceived social problem. They are important to social problems because they help shape how people think about and perceive troubling conditions, they inspire people to become involved in civic or political organizations that work to improve troubling conditions, and they shape people’s ideas about what ideal solutions to social problems look like. Activists sound the alarm, shape the narrative, and provide a vision for change. This makes them important actors in the social problems process. Social movement organizations, (SMOs) are the formal institutions that activists build to organize their work.

It’s important to keep in mind that activists are often political outsiders. There are some exceptions to this, but people usually become activists because they don’t have an insider connection that enables them to interact directly with policymakers to influence law and public policy. As political outsiders, activists often need the media to pick up their claims and disseminate them to a broader audience if they are going to have much influence on public attitudes about troubling conditions or win any changes in law or policy.

In contrast, experts are usually political insiders. We typically see individuals with specialized knowledge, technical training, or prestigious credentials as “experts” in their field. They are routinely consulted by policymakers and invited to provide their professional opinions about policy issues for which they have relevant expertise, giving them a direct line of communication to audiences of lawmakers and the public (Best 2021).

The distinction between these two groups – activists and experts – has become increasingly blurred as activists have learned that they have more success when they create coalitions, or organizational alliances, that facilitate access to experts (McCarthy and Zald 1977). Activist groups have learned that experts are typically seen as more credible, reliable sources of information. This makes them powerful claimsmakers because we assume that they are qualified to interpret social problems and facts about them. Lacking expertise ourselves, we tend to trust interpretations provided by medical doctors, scientists and researchers, professors, and government agencies (sometimes!), and their recommendations for dealing with social problems are therefore highly influential.

This observation is not lost on activists. In addition to their persuasive advantage in claimsmaking activity, experts often have advanced knowledge about navigating the political process and identifying opportunities to influence policy issues. This type of expert knowledge is an important human resource to which activist groups must cultivate access. Formalized SMOs have an advantage at this. Formalized SMOs have established procedures or structures that enable them to perform certain tasks routinely, have bureaucratic decision-making processes, a developed division of labor, explicit criteria for membership, and rules governing subunits. In contrast, informal SMOs have few established procedures, loose membership requirements, and a minimal division of labor (Staggenborg 1988). Repeatedly, research has shown that formalized organizations are best positioned to secure the funding needed to hire skilled professionals and to carry out routine organizational maintenance (McAdam 1982; Staggenborg 1988).

The professionalization of SMOs became increasingly important to the environmental movement after passage of signature environmental protection laws in the 1970s. The National Environmental Protection Act (1970), the Clean Air Act (1970), the Clean Water Act (1972), the Safe Drinking Water Act (1974), among others, put in place a new regulatory framework that shifted the role of environmental advocacy organizations. Along with their traditional role of rallying public audiences to join demonstrations or sign petitions, many organizations also engage in lobbying, policy consultation, and litigation (Gottlieb 1993).

Some have criticized this trend, arguing that national environmental organizations have become too cozy with business opponents in their negotiations (Gottlieb 1993). However, others argue that professionalization has been necessary for securing environmentalists’ a stable position in the American political environment (Bosso 2005). Professional advocacy organizations, like the Sierra Club or the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), have an established record of credibility that informal groups lack. They are routinely invited to sit at the policymaking table when laws involving practices with environmental impacts, like fracking, are crafted.

What the Frack?

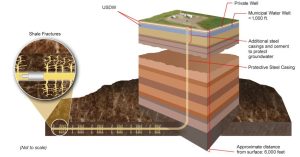

High volume horizontal hydraulic fracturing, also known as unconventional oil and gas extraction, or “fracking,” is a method of recovering hydrocarbons from tight shale formations introduced in the U.S. in the mid-2000’s. The technique involves injecting a large volume of water and sand into a well under pressure to create fractures in shale formations that release trapped hydrocarbons – oil and natural gas. The “unconventional” part of this production technique involved the combination of horizontal drilling with a 1970s method of hydraulic fracturing inside the horizontal well bore at about a mile underground, which enabled producers to access new oil and gas reserves (USGS 2019; US Dept. of Energy n.d.).

If you are the United States government, which has a vested interest in securing access to critical fuels for facilitating economic productivity and transportation, the discovery of a whole new source of energy is really great news! Under the Obama administration, the U.S. Department of Energy championed research by the National Energy Technology Laboratory (NETL) as a “game changer” for U.S. energy markets (Smith 2012; Strauss Center n.d.). They’ve really walked that line back now! But in 2011 the U.S. Department of Energy was turning themselves into absolute knots in their efforts to sell the public on fracking as the technological solution for America’s energy challenges.

If you think I’m making this up, check out the article below, archived on the U.S. Department of Homeland Security’s digital library.

In spite of the Obama administration’s enthusiasm, environmental impacts associated with this oil and gas production process, including chemical spills, surface water degradation, groundwater contamination, and induced seismicity (earthquakes) (USGS 2019), quickly inspired concern. The documentary Gasland aired in 2010. As you can see from the trailer below, it successfully painted a catastrophic and dramatic picture of the practice, and social movements opposing proposed drill sites broke out all over the place.

My research about fracking began because, fortuitously enough, the movement reached southern Illinois, where I was in graduate school, at about the same time I was trying to select a topic for my dissertation. I was pitching several potential projects to my dissertation advisor, and when I mentioned mobilization around fracking he said, “Do that, it’s going on right here. Find out where those people are meeting and go.” So, I did!

My entry into the field was through the local activist network. However, as my research progressed, I realized that there were substantial differences in the perspectives, demands, and strategic approaches of grassroots groups and national environmental advocacy organizations working on this issue in the state of Illinois. Further, there was a sizable population of landowners in southern Illinois who had conventional oil wells on their properties and saw many benefits of oil and gas production that used the new horizontal drilling techniques. These included a reduced land footprint, ability to locate wells on the periphery of one’s property, and the ability to extend the profitability of royalty revenues from wells that were declining in productivity. This ultimately made it important to conduct interviews with stakeholders from a variety of organizations and with differing political stances on the issue.

Fracturing Illinois

In this story, there are four main characters: grassroots, informal activist groups; professionalized environmental advocacy organizations; pro-oil counter-movement groups; and the poor Illinois Department of Natural Resources (IDNR) caught up in the fray.

The grassroots activist groups have a special flavor in southern Illinois, where sandstone bluff formations create a picturesque landscape and attract a variety of outdoor recreation enthusiasts to the Shawnee National Forest. In the 1990s activists opposed to clearcutting in the forest launched a fierce resistance, engaging in totally insane extrainstitutional tactics, like burying themselves up to the neck in dirt roads to prevent access to timber sites. No joke!

When these folks learned that the oil and gas industry was buying up mineral leases in southern Illinois, they quickly brought together a group of people who were concerned about the environmental impacts of fracking, and in January 2012 an organization was formed to serve as a local political voice on the issue – Southern Illinoisans against Fracturing our Environment (SAFE).

Additionally, the professionalized environmental advocacy sector is highly organized in Illinois, where the Chicago metropolitan area houses Midwest offices for several national organizations, include NRDC, Environmental Law & Policy Center (ELPC), Food & Water Watch, and the Illinois Sierra Club. Since these professionalized organizations routinely participate in environmental policymaking in Illinois, they were quick to recognize that gaps in the existing Illinois Oil and Gas act essentially gave developers free rein with unconventional extraction techniques in the state. As one organizer told me, “It was about the level of paperwork that it took to get a dog licensed” (Personal interview, NRDC).

At first the informal and formal anti-fracking advocacy arms worked somewhat separately, with grassroots groups raising a ruckus downstate and the professional advocacy organizations introducing regulatory legislation upstate. Their actions were complimentary since the activities of informal groups raised visibility around the issue and increased pressure for regulations on the oil and gas industry. As the legislative process advanced, grassroots groups grew interested in having a seat at the policy table, but they quickly found that it was difficult to play ball in the state political arena. As one SAFE activist told me,

The thing about this whole SAFE and grassroots environmental movements and, in this particular case, fracking movements, we’re all in way over our heads. Alright? And we are trying very hard to float. To breathe. To keep our head above water. And it involves learning scientific shit about air pollution, radioactivity, methane migration, global warming, yada, yada, yada. You know and I’m no scien- hell I’m a high school dropout, ok? (Personal interview, SAFE).

When a group of citizens concerned about an acute social problem form an activist group, they face a steep learning curve and lack access to political and scientific expertise. By working with professionalized advocacy organizations, in this case in the environmental sector, grassroots activists were able to expand their resource base and their mobilization capacity.

This became particularly apparent during the administrative rulemaking that followed the 2013 passage of the Illinois Hydraulic Fracturing Regulatory Act, whose implementation fell to the IDNR. The IDNR released its first draft of administrative rules on November 15, 2013, which kicked off a 45-day public comment period for Illinois residents to submit written critiques of the rule document. I attended five public hearings held across the state, at which residents provided verbal comments about the rules.

During the public comment period, professional advocacy organizations leaned on their digitally networked membership lists, emailing petitions and daily comment suggestions to thousands of members. Meanwhile, grassroots fractivists stormed the public hearings, turning them into demonstration sites. Many speakers read pre-written comments prepared by staff from professional advocacy organizations, who had the financial resources to hire technical and legal experts to dissect the rule drafts and prepare polished statements.

Because of these activities, IDNR received over 37,000 public comments on the first draft of their hydraulic fracturing rules. Imagine the poor schmuck interning at IDNR from 2013-2014 who had to scan each of the 37,000 comments – including a series of anti-fracking Christmas cards like the one pictured below – into public record. What a gig!

The large volume of comments IDNR received indicated that its fracking rules had generated an unusual amount of public interest and warranted a careful response to public comment (Personal interview, IDNR). IDNR’s 369-page response and rule revisions took ten months to compile.

Infuriated at the delay of rulemaking (and thus, oil and gas development), residents with oil interests in southeastern Illinois formed a counter-movement organization, Opportunities in Land (O.IL), to represent their perspective. At a town hall meeting hosted by O.IL in White County, a leading oil-producing county in Illinois, an invited speaker urged local fracking supporters to become a more visible political presence, saying,

Without question, the least represented part of this state on this debate is where it’s gonna happen. And it just ticks me off. So that’s the reason we’re trying to get the word out. We want people to have their voices heard (Field observations, O.IL town hall meeting).

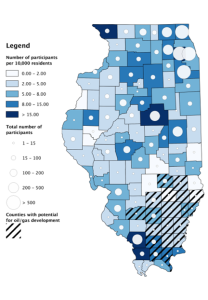

He had a point! A colleague and I obtained copies of all 37,000+ comments, which IDNR is legally required to make available to the public. We analyzed the names, addresses, and organizational affiliations of the individuals who submitted comments and discovered that most comments opposing fracking were submitted by individuals and organizations from northern, urban centers of Illinois (Dokshin and Buday 2018). When people from southern Illinois did submit comments, they were less likely to list an organizational affiliation. This suggests that the organizational networks of professionalized advocacy organizations were important for getting extra-local actors involved, amplifying the voices of their grassroots activist allies.

But there are also some thorny ethical questions raised by this activist strategy. To what extent did the voices of local landowners, who were counting on the revenue from oil production on their properties, get drowned out in the process? Describing his frustration with the rulemaking, one member of O.IL told me,

I think when you grow up around the oil industry and you grow up in an area that people work hard, enjoy what they’re doing, and they’re providing for their family, you look at an industry like the oil industry here and you see that as something that’s been stable for a long time, that’s provided for people… As an outsider looking into the situation- maybe you live in Illinois and you’re looking over here, you don’t have any activity in your area and haven’t been associated with it. What you need to do is you just need to look a little harder at both sides. (Personal interview, O.IL)

Thousands of people from Chicago and Champaign-Urbana didn’t take a harder look. They fired off their daily electronic comment and applauded the organized effort to swamp the IDNR.

In the end, by the time IDNR did finally manage to finish their rules in 2014, the oil market had tanked. The per-barrel price of oil plunged to $44 – well below the range at which exploratory drilling can be profitable. Many oil and gas companies allowed their mineral leases to expire and gave up on drilling in Illinois. Only one company pursued a drilling permit in 2016, but they withdrew their permit application in 2017, saying that the state’s regulations were prohibitively complex and expensive.

From the fractivists’ perspective, the story of fracking Illinois is one of success. But, I wondered, at what cost?

In leveraging their digital mobilization networks around this local land use dispute, extra-local activists associated with professionalized organizations may have exacerbated political polarization in the region. After all, activists need to polarize issues for people to feel strongly “for” or “against” something, and therefore willing to join the cause. Polarization is the point of using claimsmaking strategies that emphasize the most alarming, morally egregious, emotionally exciting viewpoint about a social problem. Got a doctor to deliver the news? Excellent! Really big numbers? The more the merrier!

The nuance of grey areas and ethical complexity are contraindicated to political mobilization. Studying this issue made me question whether extra-local advocacy organizations may deepen community vulnerabilities when they get involved in local movements. Could widening the gap between local opponents and supporters of fracking make it more difficult for southern Illinoisans to take actions to protect themselves from exploitation if interest in oil and gas development ever returns?

In Sum

In this chapter, we have examined the importance of activists and experts in the claimsmaking process, including who they are and the nature of their roles in the process of making social problems. We have also discussed the relative advantage experts experience as claimsmakers because they often have a direct line of communication with public and policymaking audiences, whereas activists are reliant on the media to carry their claims. This produces differing strategic trajectories for research mobilization and political action between formal and informal SMOs.

I used examples from my research on fracking in Illinois to illustrate these dynamics. The central lessons I took away from this story were about the importance of critically analyzing claims to identify the mobilization intentions of activist and expert claimsmakers. Who are they trying to move to action, how so, and for what purpose? I also learned to listen with a careful ear for whose voices are represented, as well as whose may have been left out. I don’t mean to suggest that you should never join a social movement or support organizations advocating for causes you support, but I am suggesting that you stop and make sure you are in touch with basic facts of the matter that account for differing experiences and interests before you add your signature to the petition.

References

Best, Joel. 2021. Social Problems, 4th Edition. New York: W.W. Norton.

Bosso, Christopher J. 2005. Environment, Inc.: From Grassroots to Beltway. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas.

Dokshin, Fedor A. and Amanda Buday. 2018. “Not in Your Backyard! Organizational Structure, Partisanship, and the Mobilization of Nonbeneficiary Constituents against ‘Fracking’ in Illinoi, 2013-2014.” Socius 4: 1-17.

Fox, Josh. 2010. Gasland. Toronto: Mongrel Media.

Gottlieb, Robert. 1993. Forcing the Spring: The Transformation of the American Environmental Movement. Washington, DC: Island Press.

McAdam, Doug. 1982. Political Process and the Development of Black Insurgency, 1930-1970. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

McCarthy, John D. and Mayer N. Zald. 1977. “Resource Mobilization and Social Movements: A Partial Theory.” American Journal of Sociology 82(6):1212–41.

Meyer, David S. 2015. The Politics of Protest: Social Movements in America, 2nd Edition. New York: Oxford University Press.

Staggenborg, S. 1988. “The Consequences of Professionalization and Formalization in the American Labor Movement.” American Sociological Review 53(4):585–605.

Smith, Christopher A. 2012. “Producing Natural Gas From Shale.” US Department of Energy. Accessed 11 September 2022 (https://www.energy.gov/articles/producing-natural-gas-shale).

Strauss Center. n.d. “The U.S. Shale Gas Revolution.” University of Texas at Austin, Energy and Security. Accessed 11 September 2022 (https://www.strausscenter.org/energy-and-security-project/the-u-s-shale-revolution/).

US Department of Energy. 2011. “Shale Gas: Applying Technology to Solve America’s Energy Challenges.” National Energy Technology Laboratory (https://www.hsdl.org/?abstract&did=8711).

US Department of Energy n.d. “Hydraulic Fracturing Technology.” Office of Fossil Energy and Carbon Management. Accessed 11 September 2022 (https://www.energy.gov/fecm/hydraulic-fracturing-technology).

US Geological Survey. 2019. “Hydraulic Fracturing.” USGS Water Resources. Accessed 11 September 2022 (https://www.usgs.gov/mission-areas/water-resources/science/hydraulic-fracturing).

To motivate people to participate in a social movement (Meyer 2015).

Political activities that are inside of government-approved channels, institutions (Meyer 2015: 13-14).

Political activities that are outside of government-approved channels, institutions (Meyer 2015: 13-14).

The rhetorical work of bringing the public’s view of a social problem and its solution(s) into agreement with activists’ (Meyer 2015).

Structural or cultural conditions that facilitate or impede the opportunities available for challenging groups to introduce demands for change (McAdam 1982).

The work of gaining access to the human, material, cultural, and organizational assets an aggrieved group must have to launch a political challenge (McCarthy and Zald 1977).

People who take action to remediate a social problem (Best 2021: 20).

Organizations that formalize activists’ work (Best 2021; Meyer 2015).

Individuals who “possess especially authoritative knowledge” and are therefore perceived to be credible claimsmakers (Best 2021: 20).

Formal and informal alliances between organizations with similar interests that facilitate exchanges of resources and build the collective capacity of cooperating entities (McCarthy and Zald 1977).

Movement organizations with established procedures or structures that enable them to perform certain tasks routinely, have bureaucratic decision-making processes, a developed division of labor, explicit criteria for membership, and rules governing subunits (Staggenborg 1988).

Movement organizations with few established procedures, loose membership requirements, and a minimal division of labor (Staggenborg 1988).