5 Making Social Problems

Learning Objectives

In this chapter you will:

- Define “claimsmaking” in social problems.

- Identify the mechanics of a claim.

Every semester I ask students to take a photo of something that represents a social problem to them. This photovoice exercise helps me understand the perceptions, prior knowledge, and assumptions you are bringing into this class. Often when I ask students to do this, they take very different images covering a wide range of contemporary troubles. More recently, the photos students submit fall into a few broad categories corresponding with current events.

For example, in 2024 students overwhelmingly submitted pictures about litter and waste, unhealthy diets, and worker shortages limiting snow removal.

This tells me that the information environment students are navigating has become highly saturated. There are a handful off issues that are getting a concentrated amount of attention and dominating the conversation about what we should be concerned about.

Claimsmaking is a process in which people concerned about a troubling condition make assertions that a problem exists and attempt to persuade public audiences that they ought to be concerned, too (Best 2021; Loseke 1999). In the 21st Century information environment, it easy to amplify claims about troubling conditions using digital communication networks. Email listservs and social media give claimsmakers access to broad audiences with the click of a finger. Forget knocking on doors or paying for expensive glossy mailers. Today all you need is an Instagram account to raise a ruckus.

With the heightened ability of claimsmakers to circulate alarming rhetoric about social problems, it’s important to be able to critically analyze claims so that we can avoid reacting emotionally and instead rationally assess the merit of a claim. To learn to do this, we’ll consider the typical structure most claims follow, persuasive characteristics of claims, and we’ll look at a few recent examples of the uses and abuses of statistics in claimsmaking activity.

Anatomy of a Claim

There are sociologists who have built entire careers out of rhetorical analysis, studying the persuasive claimsmaking activity around social problems. Their work provides a helpful guide in breaking down the typical structure, or pattern, that claims about social problems follow.

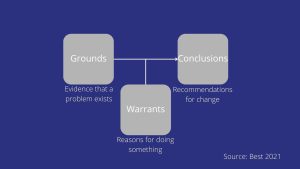

Joel Best (2021) breaks the anatomy of successful claims into three parts.

Grounds are statements that warn us about the severity or scope of a problem by telling us who is affected, how, and painting a picture of the extent of harm experienced (Best 2021: 32). To establish the grounds of a claim, claimsmakers must provide a typification of the problem for us. Due to the complexities of living in modern society, we can’t possibly have direct experience with everything in our environment. Instead, we rely on typification to provide pre-formed images of typical things we do have some direct experience with – mean dogs, bossy women – and we mentally lump things we haven’t directly experienced into categories based on things we are familiar with. Loseke argues, “Claims must convince audiences that a particular type of condition [is] at hand, that is has a particular cause, that it’s frequent, and that its consequences are troublesome (1999: 72-73, emphasis in original).

So, aside from establishing that a problem is of a certain type, the grounds of a claim are also going to provide some information about who is affected (the victim) and who is to blame (the villain), and they are probably going to include a statistic, or number, that demonstrates that the problem is widespread or affects many people (Best 2021). This is not going to be a neutral number. It is going to be a really big number that makes the issue seem really bad and looks highly official. More on that in a minute. Finally, in establishing the grounds of the problem, claimsmakers will give it a name that serves to both reinforce the problem’s typification and give us a nifty phrase for talking about it – a hashtag or handle for the issue, if you will.

Warrants are statements telling us why something ought to be done about the problem and typically appeal to broader ethical or moral principles as they issue a call to action (Best 2021: 37). The warrants of a claim are at the heart of its persuasive action and do the heavy lifting in generating a sympathetic response to claimsmaking activity. Warrants rely on the characterization of victims and villains established in the grounds of a claim and are more successful at inspiring sympathy when the victim is a person in a “higher moral category” (Loseke 1999: 76), such as a devoted churchgoer or a hard-working student, who has been harmed through no fault of their own. In contrast, it’s really hard to inspire sympathy for victims who are socially deviant – undocumented immigrants, drug users, sex workers – because they are violating moral and legal principles of our society, regardless of the harm they may experience through various conditions of their lives. Warrants, then, contribute to the work claims do to typify problems for us by providing a narrative, or story, about the problem that persuades us to see the issue as morally troublesome and worthy of corrective action.

Conclusions tell us which action(s) claimsmakers think should be taken to resolve the troubling condition (Best 2021). Conclusions are a key element of the persuasive argument made in a claim, providing recommendations for action and policy. It’s not enough to just convince people that the problem exists, as hard as that work may be. Claimsmakers who fail to convince their audiences that action is both needed and possible will make little progress in resolving the problem (Loseke 1999). Successful claimsmakers will therefore provide direction for the moral outrage they have stirred up by holding rallies or demonstrations, circulating petitions to sign, advocating for changes to laws or institutional policies, collecting donations, and so forth.

The next time you encounter alarming news about a widespread, morally troubling problem that makes you want to Snap at all your friends, hit pause and take a closer look. Recognizing the structural elements of a claim helps dislodge our dramatic instincts and kicks our critical thinking skills into gear, enabling us to move from emotional reactions to analytic reasoning. I’m not suggesting that you shouldn’t care about social problems, but I am pointing out that there are a whole lot of alarming claims being made at a given time, some of which call for quite drastic action. Before you hop on a bandwagon, maybe take a minute! Be aware that someone is trying to persuade you and think about what they want from you and why. Do some additional digging and make sure you’ve got the basic facts, starting with a critical examination of that statistic I mentioned earlier.

“Damned Lies and Statistics”

I want you to take a minute to consider this statistic:

“Every year since 1950, the number of American children gunned down has doubled.”

Pause a minute and write a few notes about your initial thoughts and/or questions about the statistic.

It’s an alarming number that tugs at our sympathy for innocent children, for sure. Did anyone work out the math on what this would actually look like?

Let’s say there was one gun-related child death in 1950. If that number doubled every year, there would be two deaths in 1951, four in 1952, eight in 1953, and so forth. That’s an exponential rate of growth.

Fast forward to 1965, there would have been 32,768 children who died from gun violence. One problem: the actual number of all criminal homicides in 1965, including both adult and child victims, was 9,960. Oopsy daisy.

By 1970, we’d be looking at over one million child deaths from gun violence for the year. By 1980, there would be one billion. That was more than four times the total U.S. population in that year.

It gets better. By 1983, there would be 8.6 billion child shooting death, which is about twice the Earth’s population at that time.

Should I stop? By 1987, the number of children killed by guns would be 137 billion, which is more than the total estimated human population throughout all history (110 billion).

Just one more. By 1995, the year the statistic was published, over 35 trillion children would have been killed by guns.

In his book, Damned Lies and Statistics, Joel Best calls this quote from a PhD student’s dissertation prospectus “the worst – that is, the most inaccurate – statistic ever” (2001).

The statistic’s origin was a statement from the Children’s Defense Fund that originally read:

“The number of American children killed each year by guns has doubled since 1950.”

Just a slight change of words completely altered the meaning of this sentence, creating an impressive but misleading statistic on gun violence. Numbers are powerful, especially when they’re big. That’s all the more reason to subject them to scrutiny.

Best’s book is a little retro at this point, so let’s look at some contemporary examples. The COVID-19 pandemic presented some fabulous examples of claimsmaking activity as medical professionals, government officials, university administrators, and their media mouthpieces frantically tried to convince the public to comply with a cascade of rapidly changing (and often contradictory) health directives.

Surprise! Here is a reading assignment within a reading assignment that has some great examples of the uses and abuses of COVID statistics. None of the statistics presented were outright lies. They were all facts, but the way those facts were visualized created misleading perceptions. Reporting agencies made it seem like things were getting worse or better, depending on their persuasive objectives. You can expect to discuss the article below, “Data (Mis)representation and COVID-19,” in class and see related questions on your exam.

Data visualization is a powerful, engaging method of communicating statistical results. It follows that the way data are represented can have persuasive impacts on public audiences. As consumers and producers of data, it’s really important that you can recognize data misrepresentations, or data that is being displayed in a misleading matter, so that you can avoid being manipulated or unnecessarily alarmed, and so that your own data communications maintain high ethical standards concerning clarity and accuracy.

In Sum

In this chapter we’ve unpacked the social construction of social problems a little further by discussing how social problems are brought into being as people concerned about troubling conditions:

- Make assertions, or claims, that a condition constitutes a problem.

- Work to disseminate their assertions and gain sympathetic audiences through claimsmaking activity.

- Make recommendations for actions and policy changes intended to help improve the troubling condition.

The public has a limited capacity to care about social issues, so claimsmakers must compete for attention, sympathy, and support. Claims that resonate with broad audiences because they successfully dramatize a situation or effectively relate to issues that people already care about may have a competitive edge, cutting through the clamor to become understood as social problems. However, if claimsmakers fail to attract sympathetic attention and inspire audiences to act, their issue will fall to the wayside regardless of the extent of harm the issue may objectively cause.

Claimsmaking is an inherently persuasive activity that has been amplified in recent years, which contributes to the feeling that everything is going to Hell in a handbasket. We are constantly confronted with alarming statistics about social problems, some of which are presented in misleading ways intended to align our view of the problem with that held by claimsmakers. For the sake of our sanity, it therefore serves us to hit pause and activate our analytic thinking when we are confronted by claims. Breaking a claim into its components helps us step back and think about the persuasive purpose of the claimsmaker so that we can make rational, informed decisions instead of reacting emotionally.

References

Best, Joel. 2021. Social Problems 4th edition. New York: W.W. Norton.

—– 2001. Damned Lies and Statistics. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Engledowl, Christopher and Travis Weiland. 2021. “Data “(Mis)representation and COVID-19: Leveraging Misleading Data Visualizations for Developing Statistical Literacy Across Grades 6-16.” Journal of Statistics and Data Science Education 29(2): 160-164.

Loseke, Donileen R. 1999. Thinking About Social Problems: An Introduction to Constructionist Perspectives. New York: Walter de Gruyter, Inc.

The act of bringing a troubling topic to the attention of others (Best 2021; Loseke 1999).

A statement that makes a persuasive argument that a condition is troubling and needs to be fixed (Best 2021; Loseke 1999).

The people who are making the claims (Best 2021; Loseke 1999).

The study of persuasion (Best 2021: 30).

Assertions of fact arguing that a problem exists and offering supporting evidence (Best 2021: 32).

Pictures in our heads of the types of things that we have direct experiences with, which we use to make inferences about similar things we have no direct experience with (Loseke 1999: 16).

People who experience harm through no fault of their own and deserve our sympathy because they are basically good (Loseke 1999).

People who cause harm for no good reason and are therefore an object of moral condemnation (Loseke 1999).

A number often used in a claim to establish that a problem is widespread or frequently occurring (Best 2021).

The title given in to a problem in a claim to reinforce its typification and establish language for speaking about it (Best 2021).

Moral appeals that justify doing something about a troubling condition (Best 2021: 37).

Statements that specify what should be done about the perceived problem (Best 2021: 39).

Distortions in data visualizations that lead to inaccurate conclusions, often for persuasive purposes (Buday 2022).