8 Writing “Eyeball To Eyeball”: Building A Successful Collaboration

Rebecca Ingalls

“Yesterday, all my troubles seemed so far away.”[1] The speaker in the song, “Yesterday,” laments his loneliness, but the mastermind behind one of the most successful and most covered songs in music history was actually a team of two individuals: Beatles members John Lennon and Paul McCartney. While they might have made it look easy, and while the rewards were huge, these collaborators worked diligently and systematically to create, share, and merge their ideas into what we know today as “Hey Jude” and “Eleanor Rigby.” In one of the later interviews that Lennon did with the mainstream press, he was asked to describe his collaborations with McCartney: “[McCartney] provided a lightness, an optimism, while I would always go for the sadness, the discords, the bluesy notes” (Sheff 136–37). Lennon referred to this process as writing “eyeball to eyeball”:

Like in “I Want to Hold Your Hand,” I remember when we got the chord that made that song. We were in Jane Asher’s house, downstairs in the cellar playing on the piano at the same time. And we had, “Oh you-uu . . . got that something . . .” And Paul hits this chord and I turn to him and say, “That’s it!” I said, “Do that again!” In those days, we really used to absolutely write like that—both playing into each other’s nose. We spent hours and hours and hours . . . We wrote in the back of vans together. . . . The cooperation was functional as well as musical. (Sheff 137)

In this merging of minds between artists and friends, one would write a verse, and the other would finish the song; one would start the “story” of a song, and the other would see the plot through (Sheff 139–40). Ultimately, this collaboration would form the core of a band that would produce countless number one hits, sell over one billion records, and reinvent rock and roll (“The Beatles”).

For Lennon and McCartney, the writing stakes were high: deadlines, fans, their integrity as musicians, a potentially galactic payout of profits and stardom. So, it wasn’t just casual loafing around and making up songs; it was inspiration and creativity that had to happen, or they wouldn’t achieve and sustain the success they hoped for. In order to create together, they had to establish and rely on some important elements: an openness to one another’s independent interests and experiences, an ability to communicate productive feedback, a trust in their shared goals. With these components of collaboration working for them, they were able to establish a process of tuning in to one another’s skills and creativity that was so powerful, Lennon could still remember the moments of inspiration, the words they exchanged, and the obscure locations where it all happened. Together, in their collaborative song writing, they were an even greater musical force than they were as solo writers.

In addition to this famous duo, there are many other famous writing collaborations that have produced some celebrated work in popular media: Matt Damon and Ben Affleck (Good Will Hunting), Google co-founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin, Simon and Garfunkel, the Indigo Girls, Dr. Dre and Snoop Dog, Tina Fey and Amy Poehler, the Farrelly brothers (There’s Something About Mary), Larry David and Jerry Seinfeld. On a global scale, writing teams have produced memorable Presidential speeches, garnered funding to fight worldwide diseases like AIDS, laid down the philosophical foundations of entire nations, and, yes, made hilarious comedy that has resonated across cultures. They have demonstrated over and over again the tremendous advantages of composing together, and the fruits of their collaborative labors are still growing today.

Your writing classroom can be a laboratory for collaborative work. Though you may be most accustomed to writing on your own, the high-impact, innovative possibilities of collaborative writing can spotlight and enhance who you are as an individual, and how creative and original you can be, when you allow your ideas to mix and develop with others’ ideas. This chapter aims to encourage and support your collaborations from beginning to end by offering insight and tools that you can use to engage work that is challenging, productive, and even enjoyable. You’ll learn about some mindful, structured strategies that focus on planning, communicating, and working with a diversity of perspectives in a group of equal members. You’ll also hear from students who—like you—have experienced the ups and downs of composing with others, and who have found something unique in the spirit of working together.

Why collaborate? you might ask. What’s in it for me? The collaborative work that you take on now in college prepares you for the challenges of higher stakes teamwork that you will encounter in your professional life. The realms of publishing, medicine, law, scientific research, marketing, sales, education, architecture, engineering, and most others show us that collaborative work, and very often collaborative writing, is key to expressing the voices of employees to one another, creating productive change, following legal protocols, communicating with clients, and producing cutting-edge products. Whether it’s the composition of a patient’s medical history, a legal brief, a plan for a company’s expansion, a proposal for a city playground, an application for federal research funds, the instruction manual for repairing a submarine’s navigation system, or a marketing campaign for a new computer, the requirements of many professional writing tasks necessarily call upon a group of people to create, revise, and polish that writing together. The combined efforts of individuals with specific expertise and common goals help to produce the highest quality writing for audiences that expect nothing less.

And, for those of you who have the kind of Lennon-McCartney hopes of making a giant impact on your world, you never know where the ideas of a few smart students working together may lead . . .

Getting Started

As you read, you may be tapping into your memories of group work— some of these memories may be positive, and some may be less so. Some of you may have some memories of collaboration that leave you wondering if it can really work at all; what if a group just can’t seem to get it together? How is it possible to make sure each group member carries an equal load? Others may have hopeful memories of a project or two that went well . . . maybe even really well. There was a motivation, a synergy, a collective feeling of pride among you. What we remember about our collaborative experiences can shape how we see collaboration now, so it’s useful to dig into those memories and reflect on them before you get started. Once we know why we see collaboration in certain ways, and once we share some of those stories, we can begin to create the kind of common ground that collaboration asks for.

Your Experiences Matter

Take some time to think through some of the collaborative work you’ve done in the past. Without worrying about mechanics or organization—spend fifteen minutes just writing about one or two experiences you’ve had. After you’ve spent some time writing, go back and re-read your freewrite, paying careful attention to the emotions you read in your words. Do you see inspiration? Anxiety? Pride? Frustration? Confidence? Confusion? What were the sources of these emotions in your experience? How do they shape the ways in which you view collaboration today?

Now, spend some time thinking about how those collaborations were set up. Specifically,

- What was the purpose of the collaboration?

- How was the group selected?

- How did you make creative and strategic decisions?

- How did you divide labor?

- If there were tensions, how did you resolve them?

- How did you maintain quality and integrity?

- In what ways did you offer praise to one another?

- How did you decide when the project was complete?

In my classroom, I often ask students at the beginning of a collaborative project to write about their experiences, and I have found that many of them measure the effectiveness of collaborative work according to those experiences. And why wouldn’t they? Experiences are powerful lenses, and they can help us to stay positive, as the one student who recalled, “Working in groups has worked well for me most of the time.” They can also make us more skeptical or even fearful of future collaborative experiences, as was the case with another student, who reflected, “I did my best to get out of them, and find a way to work alone. . . . Many times, it was one person pulling the weight of a whole group, and many times that was me.”

Rather than just labeling a collaborative experience “good” or “bad,” however, we can study the answers to these questions above and think more critically about how and why collaboration succeeds or fails. We can also take a more specific look at our own actions and tendencies for working in a group. Go back to that memorable collaboration, or even to other forms of group work that you’ve experienced, and ask yourself:

- What role did I play in that collaboration?

- More broadly, what role(s) do I tend to take in collaborative work? Why?

- How do I measure motivation and expectations of my group members?

- How do I measure fairness in dividing tasks?

- How do I measure success?

- How do I find the words to speak up when I want to challenge the group?

By looking at how a collaborative project was structured, and by examining our personal behavior in a collaborative situation, we can think more critically about how we might keep or change our approaches in future contexts.

Structuring the Path Ahead: Setting Up Your Project

Remember that Lennon and McCartney depended on their mutual respect, communication skills, and shared goals in their collaborative compositions. So, too, can you focus on these elements in your own collaborative work—the key is to build a structure that supports those components. Before you begin to research, design, and write your composition, prepare yourself and your group for the work ahead by considering three important steps to setting up your project: opening your mind, selecting group members, and articulating goals in a group contract.

Keep an Open Mind

Go back to the freewrite you composed about your experiences with collaboration, and re-acquaint yourself with the mindset you had about those experiences. Then look carefully once again at the ways in which that collaboration was structured. What would you change? What would you keep the same? Perhaps one of the most important approaches you can take to collaborative work is to keep an open mind; draw from your experiences, and be willing to learn something entirely new. Do not only assume that because a certain approach did or did not work in the past it will or will not work in the future. For example, though your group’s biology lab in your junior year of high school seemed to write itself, you may encounter new writing challenges now that you’re working with a brand new group of students. Likewise, though the senior year capstone collaborative project seemed dominated by the one student who struggled to incorporate others’ ideas, you may find that your group members in college are less willing to be silenced. A brand new collaborative situation offers you the opportunity to see yourself and your peers as credible sources of information. Each of you has something to offer, and whether your offerings coincide or clash, the valuable chance to learn from one another is there. If each group member pledges to allow for the thoughts and ideas of other members, you’ve gotten off to a promising start.

Selecting Group Members

A teacher will often invite students to decide how they want to be grouped in collaborative work. If this is the case, think carefully about this critical part of the project. Want to work with your friends? Sometimes this is a great plan; after all, we often choose our friends based on common interests and views on the world. But consider the insight of teacher and scholar Rebecca Moore Howard. In her work on collaboration, Howard describes one collaborative assignment in which she explained to her students

that choosing their own groups would allow them maximum comfort but would leave some students feeling unloved, and . . . that the comfort of self-chosen groups could sometimes result in poor decision-making, with too much consideration for established relations and not enough for the collaborative project. (64–65)

If you decide to work with your friends, it could be the best collaboration ever. But it could also put additional pressures on the friendships, which may detract from the tasks at hand. And what about those students who don’t have any close friends in the class? With these cautionary notes in mind, Howard’s students decided to be randomly grouped together. However you decide to group your project, go back to that “Keep an Open Mind” idea and consider how you might populate your group most effectively for the benefit of the class, the project, and your own development as a writer and student.

Establishing a Group Contract

Once you’ve established your group, there is an important step to take before you dive into the work, and in many ways it acts as your first collaborative writing activity: the group contract. This contract serves as a kind of group constitution: it lays out the collective goals and ground rules that will adhere group members to a core ethos for productive, healthy, creative work. It also gives you a map of where to begin and how to proceed as you divide the labor of the project. In composing your contract, consider the following issues.

- Understanding the project at hand. From the get-go, group members should have a clear, shared understanding of what is expected from your teacher. Engage in a discussion in which you articulate to one another the goals of the project: what is the composition supposed to accomplish? What should it teach you as the authors? Discuss the parameters of the project: form, length, design, voice, research expectations, creative possibilities.

- Communication practices. Spend a few minutes discussing together what “good communication” looks like. This conversation may offer you a valuable opportunity to share some experiences and get to know one another better. Once you have outlined your standards for communication, establish ground rules for communication so that your group fosters sharp listening and makes space for a diversity of ideas and perspectives. Will you meet regularly in person, or will you rely on electronic means like email, chatting, a wiki, online collaborative software like Google Docs, or Facebook? If you use email, will you regularly include all group members on all emails to keep everyone in the loop? How will you vote on an idea? What if everyone agrees on a concept except one person? What if tensions arise? Will you deal with them one-on-one? In front of the whole group? Will you involve your teacher? When and why?

- Meeting deadlines. Discuss your group members’ various schedules, and establish a deadline for each component of the project. Decide together how you will ensure that group members adhere to deadlines, and how you will communicate with and support one another in achieving these deadlines.

- Ethics. Discuss academic integrity and be sure that each group member commits to ethical research and the critical evaluation of sources. Each member should commit to checking over the final product to be sure that sources are appropriately documented. Rely on open, clear communication throughout the process of research and documentation so that you achieve accuracy and a shared understanding of how the text was composed, fact-checked, and edited.

- Standards. Discuss together what “quality” and “success” mean to each of you: is it an A? Is it a project that takes risks? Is it consensus? Is it a collaborative process that is enjoyable? Is it the making of friends in a working group? How will you know when your product has reached your desired quality and is ready to be submitted?

As you can see, this contract is not to be taken lightly: time and effort spent on a reliable contract are likely to save time and energy later. The contract acts as the spine of a group that is sensitive to differences of experience and opinion, and that aims to contribute to the intellectual growth of each of its members. While the contract should be unified by the time you’re done with it, allow space for group members to disagree about what is important—working with this disagreement will be good practice for you when it comes to composing the project itself. When it’s completed, be sure that each group member receives a copy of the contract. You should also give a copy to your teacher so that he/she has access in the event that you want your teacher to be involved in conflict resolution. Keep in mind, too, that the best contracts are used to define your responsibilities and enhance communication, not to hold over one another—your contract is a thoughtfully composed articulation of your goals, not a policing tool.

Working Together: Inventing, Planning, Getting Unstuck, and Checking In

Now, with your contract signed, sealed, and e-delivered to one another, you’re ready to launch into developing your project. In this section, we’ll explore some activities that will help you to make decisions about topics, carry out the specifics of project administration, resolve conflict, and re-calibrate your contract.

Choosing a Worthy Topic

In many cases your teacher may assign you the specific topic for your collaborative project; in other cases, you may actually be grouped together according to your common interests or fields of study. In still other cases, you may find yourself in a situation in which your group is composed of a diversity of interests, and where there are fewer constraints on the assignment. For example, maybe you’ve been assigned to write a proposal that offers a solution to a citywide problem, maybe you’ve been asked to work together to research and compose an analytical report on a debate in the latest Presidential election, or maybe you’ve just been asked to get together to defend one side of an issue that is important to you. In any of these cases, you’re likely to face one big question: what should your topic be?

It can be tempting to hurry past this important point in the process so that you can get down to business with the project itself. Often, students toss some ideas around and use a “majority rules” method of choosing a topic, or they might look for a topic based on how “easy” it seems rather than on how compelling it might be to research. But think about the journey you’re about to undertake, do yourselves a favor, and commit to choosing a worthy topic that is likely to keep you focused and interested for the duration of the project. Use the opportunity of many brains working together to pick a unique, fascinating topic that will stretch those brains in new ways. After all, what’s college for if not to challenge you?

One technique that can be helpful in an open-topic situation actually comes from the world of business: it is called an “affinity diagram,” and it can be useful in mapping group members’ individual interests and sketching out how those interests may be combined into categories. In their research on engineering students in first year composition, Meredith Green and Sarah Duerden found affinity diagrams to be particularly useful not just for deciding on topics, but also for resolving conflict later in the process of collaboration (“Collaboration, English Composition”). You’ll find that the affinity diagram helps you to delve deeper into the advantages and disadvantages of choosing certain topics, and helps you to imagine what it would be like to see a topic through from beginning to end. Later, too, you may find that creating this kind of diagram helps you to “see” a disagreement, as it arises in your group, in a way that talking around it, or even directly about it, doesn’t seem to capture.

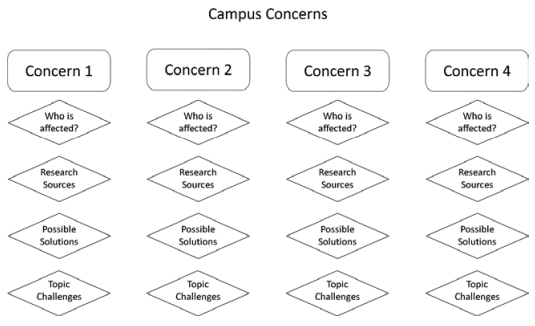

How do you begin? Let’s say your group has been asked to select a campus-wide problem and write a proposal for its solution, and you’ve got to decide together on a problem that you each agree is worth investigating. Start with a brainstorm. Each member of the group writes down on separate small pieces of paper two or more major individual concerns for your campus. Lay out all of the pieces of paper before you, and see whether you have common concerns, or whether some concerns might be related to one another. Once you’ve narrowed the list of concerns, begin to create sub-categories for each concern: effects of the problem on campus, resources for researching the problem (including primary and scholarly research), hypothetical solutions, and potential challenges in taking on the topic. Your affinity diagram might look a little something like Figure 1.

Much more than a pro-con list, the affinity diagram puts some multi-faceted wisdom into the decision-making by showing you the magnitude of your campus concerns (who is affected by the problem), the availability of sources to support your research, and the feasibility of what needs to be done to remedy the problem. Filling in these categories above may help you to see more clearly what challenges may lie ahead for you if you decide to take on any one of these campus concerns. Thus, once you’ve enriched your diagram, you can begin to see together which topics have the most promise in terms of enjoyment, challenge, and sustainability. Moreover, as Green and Duerden found to be true for their students, don’t hesitate to give the diagram some time to “incubate” (4). That is, if class time is only an hour or so, get the diagram started, but check back in with group members later in the day, or even the next day. Talk to others, do some initial online research, let the ideas marinate so that you can best represent them in the diagram before you make a decision together about which topic you want to tackle.

Project Management

Now that you’ve selected a topic you can all invest in, you’re ready to lay out work for the next few weeks. Together, divide the project into logical stages of development, taking into consideration what the composition will need in terms of its research, analysis, organizational sections, graphics, fact-checking, editing, and drafting. Also consider the responsibilities necessary for each of these stages. Again, you may find that the affinity diagram is helpful here to illustrate the major steps toward completion, the sub-steps of each, and the places where steps in the process may be combined. The diagram can be a tangible way to see or imagine the process of the project when you don’t yet have the final product in hand.

Next, divide the labor mindfully and fairly by discussing who will take on each responsibility. Think back on your experience and tendencies with collaboration. Is there an opportunity to do more listening, leading, negotiating, or questioning than you have in the past? Are there unique talents that individuals can bring to the project’s various elements? Is one of you interested in design or illustration, for instance? Is another interested in multimedia approaches to presentation? You may elect a “divide and conquer” approach, but consider, too, that some sections of the project may require a sub-set of group members, and that other sections will need everyone’s input (like research, editing, checking for documentation accuracy, decisions on design). In combining your individual skills with common goals, you’re likely to find that the work you’re doing is much greater than the sum of its parts. While individual group members’ specific skills will be spotlighted in their own ways, this plan for the management of the project should also reveal that every stage of the process gets input from each member.

When Conflict Gets You Stuck: Writing Your Way Out

Though your group contract is meant to help you to avoid or foresee conflict before it arises, you still may encounter some unexpected patches of conflict along the way that you didn’t see coming. Maybe it’s late and the group is hungry, tired, and grumpy. Maybe one group member brought some of his personal struggles with him to the scheduled meeting. Maybe another group member suddenly decides that she doesn’t like an idea you all agreed upon last week. Either way, the conflict that sneaks up on you can be challenging to work through, and it can make you all feel a little stuck.

One cause of conflict is what philosopher Richard Rorty called “abnormal discourse,” or, as Kenneth Bruffee explains, the “kooky” or “revolutionary” comments or gestures that someone might make in a group (qtd. in Bruffee 648). What does abnormal discourse look like? Well, let’s say that as a group you’re working on a proposal to improve the computer labs on campus, and you’re talking about which images to include in your composition. Someone pulls up a photograph of a group of students all sitting around a monitor, their faces lit by the screen, and most members of the group chime in excitedly that the photo does a nice job of showing how an improved computer lab might help to enhance student community. In the middle of your conversation, however, one of your group members dismissively remarks, “That’s a terrible photo. I can’t believe you all want to use it,” and then leaves the room. How rude, right? Maybe not.

You may be taken aback by what seemed like an outburst from your fellow group member. You might think that a group agreeing animatedly on a photo is yet another positive step toward the completion of your project, and you may even be annoyed and think that the naysayer is a buzz kill and will stall the project. But consider this: abnormal discourse can actually be a good thing, an opportunity for positive growth or change inside the group. In the situation described above, the student may have a very good reason for rejecting the photo, but perhaps did not want or know how to communicate disagreement in any other way. For example, maybe all of the students in the photo are Caucasian, and the student of color who rejected it is offended because he feels excluded by it. Maybe the photo is all male students, and a female group member is disappointed that her other female group members would support it. The point is, the tension that arises around abnormal discourse can be alarming and can make you feel stuck for a bit, but it may prove to be enlightening, and as a group you owe it to yourselves to get to the bottom of it. So, take a deep breath and make space for the conversation to happen. While the student’s behavior seemed to come out of left field, you may find that his resistance is actually really important to understand.

So, what do you do? Dive into the argument? Maybe. In the middle of the conflict, launching into conversation about the issue at hand may seem like steps ahead of the tense moment, so you might find some relief in writing first, then turning to one another with your concerns. You might be thinking, how in the world will we as a group have the presence of mind to stop and write about our conflict before we begin to discuss it? After all, this write-before-you-speak approach is itself a form of abnormal discourse—we’re not used to doing it in our everyday interactions, right? But you may find that writing first helps you to process your thoughts, gather your questions, calm your mind a bit before you get to the heart of the matter. You might even write this method into your group contract so that you remember that, at one point in the planning of this complex project, you promised one another that you would use this technique if you ever encountered tension.

Revisiting Your Contract

While you’ve worked hard to compose your group contract, it can be difficult to keep the elements of the contract in the forefront of your mind when you and your group members immerse yourselves in the project. Instead of moving the contract to the back burner, be sure to return to it once or twice throughout the project. In reflecting on collaborative work, one student in my class remarked, “People’s roles in the project, responsibilities, work done, that can all be adjusted, but when it is time to submit it you have no room to improvise.” The “adjustments” that this student refers to can happen when you and your group touch base with the goals you set from the beginning. You might also find that it’s useful to meet briefly as a group in a more informal setting, like a coffee shop, so that you can take a refreshing look at the status of the project so far. Specifically, you might examine the following aspects of your collaboration:

- Revisit your goals. Is your composition heading in the right direction?

- Rate the overall effectiveness of communication. Call attention to any points of conflict and how you managed them.

- Discuss the workload of tasks completed thus far. Has it been fair?

- Measure the quality of the work you think the group is doing thus far.

- Remind yourselves of past and future deadlines. Do they need to be revised?

- Raise any individual concerns you may have.

If this extra step seems like more work, consider the possibility that as you push forward with the project, your goals may change and you may need to revise your contract. This step acts as a process of checks and balances that helps you to confirm your larger goal of creating a healthy, productive, enjoyable collaboration.

Concluding Your Project: Looking Back, Looking Ahead

Collaborative Review

Before you turn that project in, remember: even if you divided it up, the completed product belongs to all of you and should get each group member’s final review and approval before you submit it. This final review includes editing for mechanics, style, and surface issues (including proper documentation, fact checking, and document layout). It can be especially helpful to go over the entire final composition together, as a group. Each person takes a turn reading aloud, while other members of the group follow along and check for errors. This shared editing session can also be an opportunity to pat one another on the back.

The Post-Mortem

That’s it, right? On to the next thing? Not yet. Too often, we progress from project to project, from class to class without pausing to think back on what we have accomplished. We often miss out on reflection of the goals we had for ourselves, neglecting to ask critical analytical questions: what did I hope to accomplish? In what ways did I grow as a person? As a student or scholar? What evidence do I have for that growth? How does this growth prepare me for what is next? When it comes to the high-impact learning potential involved in collaborative work, it can be an invaluable exercise to take stock by reflecting on the stages of the process and making sense of what you experienced. Someday, in the not-too-distant future, a prospective employer or graduate school is going to want to know, “How did you get to where you are today?” This final step in the process—called a “post-mortem”—will give you some practice at formulating an answer to this complex question.

Less morbid than it sounds, the “post-mortem” is an activity that you are likely to see in the professional world, and it involves looking back on the processes used to design/write/build the project, and reflecting on your successes, failures, and personal perspectives on the process in general. For many professionals, it is an invaluable component in understanding what does and does not work as they think about future endeavors. With truly complicated endeavors like collaboration, a post-mortem can help to give you insight that you can only get once you’re on the other side of your project. Here are some guiding questions:

- Was your project a success? If so, why? If not, why?

- What were some of the most poignant lessons you learned about yourself?

- What surprised you about this collaboration?

- What might you have done differently?

- In what ways did this collaboration change or maintain your perceptions of collaborative work?

- How would you instruct someone else in the process of collaboration?

Once you’ve done your own reflecting, take your observations back to your group, and discuss together what you’ve concluded about the process. Not only does this final step bring some healthy closure to the project, but it also opens up opportunities for resolution of lingering conflict, mutual recognition of your accomplishments, and, for those of you who’ve got an especially good thing going with your work, a conversation about possibly taking your project beyond the classroom.

What Difference Does a Mindful Collaboration Make?

Does it really make a difference to do all of this prep-work and strategizing and management and reflection? I wanted to find out. Several months after my students completed a collaborative project, I did a kind of post-mortem by anonymously surveying them to get their views on collaboration. I was curious: most of them had never before taken these structured steps toward the preparation, management, and reflection on their group work. I learned from their pre-project reflections that most had worked in groups without talking about goals or communication strategies, making assumptions that their group members knew what they had to do and why. They had only known how to “launch in” and (gulp) hope for the best. And for many of these students, tensions loomed from the start. Would these new strategies change their views?

In my survey, I asked them,

- How would you rate the importance of collaboration in the university classroom?

- What do you think are the most important ingredients for successful collaboration?

- Did this collaborative project change the way you viewed collaboration before?

- How will you approach collaborative work in future academic and professional endeavors?

- How would you advise entering college students to approach collaborative work?

Despite even the most negative of experiences some students described before they began their group work, a majority of those who completed the survey rated collaboration as either “very important” or “extremely important.” What’s more, several of the students’ responses emphasized the goals behind collaboration, and many who were initially concerned about group work came to see collaboration more positively than they had before. Take a look at what some of my students wrote:

At first I felt like learning to work with someone really didn’t matter. I was fine doing the work on my own. I learned in my project that it is indeed very important.

I believe the collaborating in a university classroom is important because it prepares you for the difficulties that you will have to face with collaboration in the work field in the future. Having experienced many obstacles and difficulties while working with assigned partners and group members I know that learning to resolve these issues is a social skill that will be extremely helpful in the future.

Integral to the collaboration process is being able to understand one another, and have the patience to see what others are saying.

I feel that the most important ingredients for successful collaboration are communication, as well as compensation. Group members must be sure to communicate amongst themselves—relay problems, conflicts, concerns, and comments amongst each other. Moreover, if a given group member is having trouble completing his/her part, then the remaining members must at least make an effort to help the troubled group member.

I thought that the most important parts were an ability to listen to your peers and to also find a way to organize the group such that each person contributed to the discussion.

One aspect that can make everything a lot easier is organization. When you are organized, you save time, and everyone is able to be on the same page. The [project] gave the opportunity for students to get organized and figure how the group is going to function.

I think when you collaborate on a project it is not always going to work perfectly with people who have the same ideas as you. In order to be successful you all need to be able to negotiate and work together for a common goal.

Communication, structure, negotiation, organization, deadlines. These aspects stand out for these students as some of the most important elements of successful collaboration. While they may seem like common sense, you probably know by now how challenging it can be try to juggle all of these conceptual balls in the air when you don’t have a mindful structure to guide you. The invention, management, and reflection tools we’ve talked about in this chapter can help to form the backbone of a creative, communicative, and rewarding collaboration.

Though flying solo can produce some extraordinary individual work, we might again heed the words of Lennon, who describes his first meeting with McCartney: “I thought, half to myself, ‘He’s as good as me.’ I’d been kingpin up to then. Now I thought ‘If I take him on, what will happen?’ . . . The decision was whether to keep me strong or make the group stronger. . . . But he was good, so he was worth having. He also looked like Elvis. I dug him” (Norman 109). Lennon asked himself: what will happen? Ask yourself the same thing when you begin a group project. It could be something pretty good. It might also be something great.

Discussion

- Does the collaborative experience described in this essay at all resemble any joint activity you have engaged in? A team, a club, a group? Being in a family, working with a best friend to create a project, a world, a fort, or planning an event? Write about any part of this process that you have experienced. What appeals most to you about this structured approach—something that you are familiar with? What about the parts you are unfamiliar with—what would you like to try and why?

- The essay uses a powerfully successful partnership to describe the possibilities of group work. How can you apply what you know of great partnerships to the process of group work modeled here? Would you want to try working with a partner within a group? How could you apply this same process for working with one other person?

- As a class, create a survey of previous collaborative experiences based on the questions the essay asked you to write about in the section, “Your Experiences Matter.” Take the survey, tally the results, and discuss as a class what you have found. How can your understanding of your own past inform your construction of the future? What did you notice when you started to talk about your past experiences together?

- The section, “When Conflict Gets You Stuck,” invites you to see conflict as an opportunity in collaboration. Where do you see this approach to conflict happening in the public sphere? What are some of the challenges and benefits of taking this perspective?

- What’s your “post-mortem” for this chapter? How can you apply the ideas in this chapter to your own reading/learning experience?

Works Cited

“The Beatles Biography.” Rolling Stone Music. 28 March 2008. Web. 18 Sept. 2010.

Bruffee, Kenneth. “Collaborative Learning and the ‘Conversation of Mankind.’” College English 46.7 (1984): 635–52. Print.

Green, Meredith, and Sarah Duerden. “Collaboration, English Composition, and the Engineering Student: Constructing Knowledge in the Integrated Engineering Program.” Proceedings of the 26th Annual Frontiers in Education 1 (1996): 3–6. Web. 15 Sept. 2010.

Howard, Rebecca Moore. “Collaborative Pedagogy.” A Guide to Composition Pedagogies. Ed. Gary Tate, Amy Rupiper, and Kurt Schick. New York: Oxford UP, 2001. Print.

Ingalls, Rebecca. “Collaborative Work in the Composition Classroom.” Survey. 10 Aug. 2009. 31 Aug. 2009.

Norman, Philip. John Lennon: The Life. New York: Harper Collins, 2008. Print.

Sheff, David. All We Are Saying: The Last Major Interview with John Lennon and Yoko Ono. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2000. Print.

- This work is licensed under the Creative Commons AttributionNoncommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 United States License and is subject to the Writing Spaces’ Terms of Use. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/us/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, California, 94105, USA. To view the Writing Spaces’ Terms of Use, visit http://writingspaces.org/terms-of-use. ↵