8 “Finding Your Way In”: Invention as Inquiry Based Learning in First Year Writing

Steven Lessner and Collin Craig

Imagine the initial meeting of your first year writing course.[1] After welcoming you to the course and going over the basics, your writing instructor prompts you and the other students to reflect on how you typically begin to think about approaching a writing assignment. Several hands raise and you listen as students begin answering. One student hesitantly states that he normally waits until the last minute to think about it and stays up all night before it’s due, working away. Another student asserts that she often has trouble choosing and then narrowing down a topic. Disagreeing about this shared response, a student sitting near you asserts that he has trouble generating more supporting ideas once he has chosen a topic to explore. Still someone else states that she tries to get ideas from the readings she is supposed to write about in essays—often without success. After hearing from these students, your writing instructor tells the class that this is a good time to start talking about invention and helpful activities to use when approaching and starting a writing assignment.

Your first year college writing course often becomes a primary place where new writing techniques and tools are presented to help smoothen your transition into college-level writing. We hope this chapter will encourage you to see the diverse invention possibilities available when beginning a writing assignment. For instance, have you ever felt a blank sheet of paper or empty word processing screen intently staring at you while you decide what to say? Learning potential invention activities for writing can help you feel more comfortable as a writer in college by giving you many more places to begin. As college writing teachers, we know that first year writing students have plenty of generative ideas to share and many insightful connections to make in their writing. Knowing that a wide range of invention activities are available to try out may be all you need to begin approaching writing assignments with more effectiveness, clarity and creativity.

In his piece entitled “Inventing Invention” from Writing Inventions: Identities, Technologies, Pedagogies, college writing professor Scott Lloyd DeWitt makes a comparison between the inventing space his father used as an engineer and the multitude of invention activities open to writers (17–19). DeWitt describes his father’s garage as a generative place where “wires, tool handles, broken toys, thermometers, an ice bucket, lamp switches, an intercom system, the first microwave oven ever manufactured . . .” are drawn on as invention tools that his father selects depending on what project he is starting and what tool will ultimately help him the most (17). Similarly, as a writer in college with many different writing assignments, you will need to think about what invention activity best helps you not only to begin specific papers most effectively, but also to generate new ideas and arguments during the writing process.

In considering your previous experiences, you may have been taught that invention “is a single art form, or a single act of creativity” (DeWitt 23). When taught in this way, readers and writers may be misled to understand invention as something that takes place in one definite moment that can’t be revisited while in the middle of writing. Viewing invention as a one time, hit or miss event does not allow the construction and development of ideas to be seen as a continuing process a writer employs throughout the act of writing. In looking at invention as a “single act,” you might miss how helpful invention can really be as an ongoing developmental practice that allows new ideas and exciting connections to be made.

The invention activities we offer in this chapter will help you begin to see invention as more than formulaic correct or incorrect approaches for producing writing. We want these invention activities to be ones that you can try out and, ultimately, make your own as college readers and writers. Let us be clear in stating that no one invention activity may work for all writers. Some of these approaches for beginning your writing assignments will be more useful than others. However, each invention activity has been crafted with you in mind and as a generative way for you to begin thinking about your writing assignments. Through the invention strategies of reading rhetorically, freewriting, focused freewriting, critical freewriting, flexible outlining, bulleting, visual outlining and auditory/dialogic generative outlining, you will begin inventing in ways that stretch your writerly muscles. You will see how beginning papers can be a process that invites you as a participant to share and build on your experiences and knowledge in productive ways. And much like Professor DeWitt’s engineering father with his tools in a garage, you will learn to choose your invention tools with care when starting to write.

Reading Rhetorically

As a college reader, finding an author’s intent is a commonly learned critical thinking strategy that works for analyzing texts. But engaged reading can also be about discovering how the writing strategies of authors are working to build an essay and convey a message. A good start towards transitioning into college-level writing is discovering what you can stand to gain as a writer from the reading process. Through directed reading, you can learn strategies for building structure and argument in your own texts. Moreover, as part of your successful development as a writer, you’ll need ample opportunity and space for creativity in your writing process. Reading with a purpose teaches you how to use creativity to generate multiple approaches to building arguments and making connections between ideas.

Rhetorical reading is our approach for understanding the tools that writers use to persuade or effectively communicate ideas. This critical reading approach will have you analyze, interpret, and reflect on choices that writers make to convey a thought or argument. Reading rhetorically develops critical thinking skills that not only interrogate ideas but also situates them within a rhetorical situation (context) and works towards determining how the message, intended audience, and method of delivery work together for the purpose of persuasion and effective communication. For example, when reading a New York Times op-ed about the war in Iraq, you might consider the traditional political stance the newspaper has taken on the war in the Middle East and how this might determine how Iraqi citizens are spoken for, or how visual images are used to invoke an emotion about the Muslim faith in times of war. You will find that the ability to perform specific analytical moves in your reading can make you

- more aware of your own intentions as a writer;

- more specific in developing methods of delivery;

- and, more cognizant of how you want your intended audience to respond to your ideas.

This critical reading exercise encourages you to think about reading as a social interaction with the writer. Take a look at an assigned reading by an author for your course. What questions might you ask the author about the writing moves that he/she makes to draw readers in?

Here are some sample questions to get you started towards reading rhetorically.

- How does the author organize events, evidence, or arguments throughout the text?

- What stylistic moves does the text do to draw readers in?

- Does the author rely on experts, personal experience, statistics, etc. to develop an argument or communicate an idea? Is this rhetorical approach effective?

- Who might we suggest is the intended audience? How does the author make appeals or cater her message to this audience specifically?

In a writing situation that asks you to effectively communicate a specific idea to a target audience, knowing how to respond will develop your critical reading skills and provide you with effective strategies for writing in multiple genres. Having a rhetorical knowledge of how genres of writing work will also prepare you with tools for generating inquiry-based writing for multiple audiences.

A Rhetorical Reading Activity

Below is an excerpt from Gloria Anzaldua’s “How to Tame a Wild Tongue,” an autobiographic text that demonstrates how the author finds her identity as Chicana, shaped by multiple language practices and responses.

I remember being caught speaking Spanish at recess—that was good for three licks on the knuckles with a sharp ruler. I remember being sent to the corner of the classoom for “talking back” to the Anglo teacher when all I was trying to do was tell her how to pronounce my name. “If you want to be American, speak ‘American.’ If you don’t like it, go back to Mexico where you belong.”

“I want you to speak English. Pa’ hallar buen trabajo tienes que saber hablar el ingles bien. Que vale toda tu educacion si todavia hablas ingles con un ‘accent,’” my mother would say, mortified that I spoke English like a Mexican. At Pan American University, I and all Chicano students were required to take two speech classes. Their purpose: to get rid of our accents.

Attacks on one’s form of expression with the intent to censor are a violation of the First Amendment. El Anglo con cara de inocente nos arranco la lengua. Wild tongues can’t be tamed, they can only be cut out.

Asking Rhetorical Questions

Here are a few rhetorical questions you might consider asking:

- What is the rhetorical situation in which Anzaldua finds herself using different language forms? (Rhetorical situation refers to the context, intended audience, and purpose for writing.)

- Does Anzaldua’s writing attempt to invoke an emotional response from its readers?

- What makes Anzaldua credible to speak about language practices as a condition of access into a community?

- Does the author make any logical appeals to persuade readers?

- What assumptions about culture can we make based on the content of Anzaldua’s text?

Asking rhetorical questions provokes a process of inquiry-based thinking that is useful for learning how to participate in academic conversations in a way that investigates the decisions writers make when they compose and arrange compositions. As you read, get in the habit of asking rhetorical questions about the composition of texts. This will further guide your prewriting process of brainstorming and frame decisions for how you might compose your own texts. Freewriting can be an initial invention exercise that begins your composing process.

Entering Conversations as a Writer

Freewriting

Freewriting is a warmup exercise that is designed to jumpstart the writing process. Writing professor Peter Elbow, well-known for promoting the practice of freewriting, describes freewriting as private writing without stopping (4). Freewriting is an effective prewriting strategy that allows you to explore an idea without worrying about grammar errors or coherence. This form of writing is not about developing a finished product or performing “good writing.” Many writers might use this exercise to get their brains into gear when developing ideas about a topic. If you are struggling with pinning down ideas that are at the back of your mind, freewriting enables you to explore the field of thoughts in your mind and get words down on paper that can trigger connections between meaningful ideas. Here is an exercise to get you started:

Exercise 1

Take about ten minutes to write about anything that comes to mind. The goal is to keep writing without stopping. If you are coming up blank and nothing comes to mind, then write “nothing comes to mind” until something does. Do not worry about the quality of the writing, grammar, or what to write. Just write!

Focused Freewriting

Focused freewriting asks you to write about a specific topic. It is more concentrated and allows writers opportunities to develop continuity and connections between ideas while exploring all that you might know about a subject. Focused freewriting can be useful in sorting through what you know about a topic that might be useful for outlining a writing project.

Exercise 2

Take about ten minutes to focus freewrite on one of the topics below. As with initial freewriting, write without stopping. But this time, pay closer attention to maintaining a focus and developing continuity while building upon and connecting ideas.

- What writing moves can you learn from a close rhetorical reading of Anzaldua’s text to compose your own text?

- Write about an important language practice that you participated in or experienced that is not school related.

Kelsey, a first year writer on the university basketball team, offers an example of a focused freewrite she performed in her college writing course about learning how to talk to her baby sister.

I’m not really sure what he wants us to exactly write. Like speaking a different language? Talking in different tones? Language like Amy Tan described? Well since I’m not sure, I guess that I’ll just guess and see how this works. When Mackenzie was first learning to speak, she obviously didn’t produce full sentences. She used a lot of touching, showing, and pointing. When speaking to her, it was important to emphasize certain words (that she would pick up on or understand), to make them clear to her and not allow an entire sentence or phrase to confuse her. And, when she spoke to us, it was important to not only pay attention to the word that she was saying (often not comprehendible), but watch her facial expression, and notice how she used her hand to point, gesture, etc. It was truly fascinating to watch how her language developed and grew over such a short period of time. She went from shouting out short, one syllable words, to formulating her own sentences (although often without correct tenses or order), to speaking in such a way that little observation from me or my family was needed. She continued to occasionally sometimes mix up her words, or even mispronounce them, but it is still astounding to me that she learned what so many things are, how to say them, and how to describe them, without ever attending any school. I know that this is pretty much how everyone learns to speak, but the power of simple acquisition still is fascinating. Ok so now im all out of what I wanted to say.

Kelsey begins her focused freewrite with questions that help her create a framework for making sense of non-school language practices. Using personal narrative, she is able to explore the concept of acquisition in how her baby sister learns how to communicate. She also takes moments throughout her freewrite to reflect on the literacy issues implied in her recounted story. During interpretive moments of her freewriting, Kelsey can formulate ideas she might further explore about literacy as a social practice, such as the influences of both formal education and the mundane experiences of family social life.

Critical Freewriting

Critical freewriting asks writers to think more analytically about a topic or subject for writing. When we say “critical,” we do not mean it simply as an analytical approach focused solely on creating an opposing viewpoint. We use the term critical to define a reflection process during freewriting that includes

- asking questions

- responding

- engaging with opposing points of view

- developing new perspectives and then asking more questions

Critical freewriting gives you permission to grapple with an idea and even explore the basis for your own beliefs about a topic. It involves going beyond writing freely about a subject, and placing it in relationship to larger existing conversations. For example, you might ask, “How does my stance on teenage pregnancy align with existing viewpoints on abortion?” or “What are the consequences for sex education in high schools?” Critical freewriting provides you the opportunity to use reflection and inquiry as inventive strategies towards exploring multiple angles into a writing topic.

Below is an example of critical freewriting on the benefits and possible consequences of other forms of writing, such as text messaging.

Text messaging is a kind of writing that I do to keep in touch with friends and family back home and on campus. I use it everyday after class or when I get bored with studying homework. It’s a lot like instant messaging in my opinion because it allows you to communicate without having to worry about weird silences that can happen when you run out of things to say. On the other hand I wonder about how it will affect my ability to communicate in formal settings, such as a phone interview for a job when I graduate. Often times for example when I receive a phone call I will ignore it and send a text message instead of calling back. I would say that I text message more than I actually talk on the phone. I wonder how such indirect communication might create bad habits of passivity that might cause me to miss out on all the benefits of human interaction. I feel the same way about online instant messaging. Though it is a great way to maintain contact with friends that are going to college in another state, I wonder if it makes me less inclined to initiate face-to-face communication with others on campus. Some might say that digital communication is more efficient and that you can say whatever you feel without the pressure of being embarrassed by someone’s response. I would agree but meaning in words can be understood better when hearing emotions in someone’s audible voice, right? Meh, this probably won’t change my habits of typing up a quick text over calling someone. LOL.

Here the writer takes an inconclusive stance on the pros and cons of text messaging as a form of everyday communication. Her assignment might ask her to either make an argumentative stance or to take an open-ended approach in exploring instant messaging as a language practice. In either case, she engages in a recursive (ongoing) process of questioning and answering that invents scenarios and raises issues she might explore in order to develop a working knowledge on trendy forms of technological communication.

Exercise 3

Spend ten minutes critical freewriting on one of the following topics.

- What is a type of writing that you do that is not school related? How does your knowledge about the context (people, place, or occasion) of writing determine how you communicate in this writing situation?

- How has writing contributed to your experiences as a member of an online community (ex. Facebook, Twitter, writing emails)?

Critical freewriting encourages recursive thinking that enables you to create a body of ideas and to further decide which ones might be worth researching and which themes might work together in constructing a coherent, yet flexible pattern of ideas. We value flexibility because we believe it complements how ideas are never final and can always be revised or strengthened. Flexible outlining enables this process of ongoing revision, no matter what writing stage you are in.

Flexible Outlining

Once you have engaged in freewriting, you may find it useful to use a process called flexible outlining that can help you arrange your ideas into more complex, thought provoking material. First year writing students and their comments about outlining inspired the kind of flexible outlining we encourage in the exercises below. Summing up many students’ needs to begin writing a paper in some kind of outline format, first year writer Valencia Cooper writes, “The way I start a paper usually is to organize or outline the topic whatever it may be.” Valencia used a variety of bullets and indenting when beginning her work, which suggests that flexible outlining could be more effective in terms of organizing generative thoughts for papers. Similarly using a form of flexible outlining, first year writing student Tommy Brooks conveyed that he “makes an outline and fills in the blanks.” These examples encourage you as a writer to remember that there is no right or wrong way to engage in outlining ideas as you start thinking about what directions to take your paper. We encourage you to visualize, hear, and talk through important information generated from your critical freewriting using the techniques of bulleting, drawing, and dialoguing that we detail below.

Bulleting

After generating a body of ideas from freewriting, bulleting your ideas can be the next step towards conceptualizing a map of your writing project. Organizing your thoughts in bullets can generate possibilities for how you might sequence coherent streams of ideas, such as main points, examples, or themes. For instance, if you chose to critically freewrite about writing that is not school related as prompted in Exercise 3 above, itemizing the ideas in your response through bulleting allows you to isolate prospective themes and decide if they are worth exploring. Below is an example bulleted list generated from the above critical freewriting demonstration about text messaging as an alternative writing practice.

- Text messaging allows me to keep in touch with those I am close to that live far away and nearby me as well.

- Text messaging is a kind of writing that I use everyday in situations, like when I’m bored with schoolwork.

- Text messaging is very similar to instant messaging in how it avoids weird silences that happen in face-to-face or phone conversations.

- Text messaging may create bad habits of passivity that might cause missing out on human interaction.

- Text messaging does not allow emotions to be fully understood like listening to someone’s audible voice.

Visual Outlining

After locating common themes from your bullets, try to visually think about the best way to represent the arrangement of your ideas for what we call a visual outline. This exercise will require some drawing, but please understand that visual outlining does not require you to be an artist. The point of this exercise is for you to conceptualize your paper in a new way that helps generate new ideas. Peter Elbow points out in Writing With Power that drawings connected to your writing “have life, energy and experience in them” (324).

Take some time to consider how you visualize the arrangement of your paper. Is your central idea the trunk of a tree, with other ideas expanding outward as the branches, and with details hanging like leaves? Or is your beginning idea a tall skyscraper with many small windows on the outside and hallways and elevators on the inside underlying your ideas and claims?

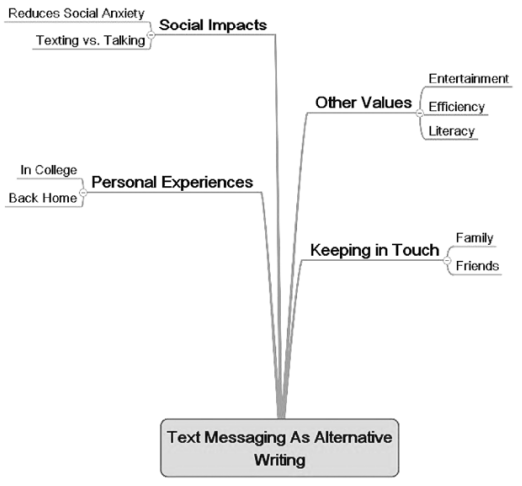

For instance, if you wanted to visualize the above bullets concerning text messaging in the shape of a tree diagram, you might write text messaging in what you draw and label as the trunk. As you continue sketching in the branches on your tree, each one should represent an idea or other evidence that supports a main claim being made about text messaging. Below, we have created a conceptual tree from the previous critical freewriting excerpt as a visual example for outlining that can be both generative and flexible. But you don’t have to imitate ours. Be stylistically creative in developing your own tree outline (see figure 1).

gure 1). Developing a tree diagram as a way of outlining ideas prompts you to see that linear approaches to orchestrating ideas are not the only way of arranging a composition at this stage. While “Text Messaging As Alternative Writing” works as the foundational theme in Figure 1, having a variety of visually horizontal alignments in this outline can eliminate premature decisions about how you might arrange your composition and which topics can be best aligned in relationship to others. Use this type of spatial alignment to make more effective decisions about how to communicate your intended message.

Exercise 4

Take some time to draw your own visual outline using the ideas developed from your critical freewriting. Think about reoccurring central theme(s) that surface. Decide which ones can be foundational in building supporting arguments or potential alternative perspectives.

Reflection

- From looking at your visual outline, what directions might you first consider pursuing in the process of developing and organizing an essay?

- In what ways did using an image as a medium for outlining allow you to think about how you might arrange your ideas?

Auditory/Dialogic Generative Outlining

We also want to suggest an interactive outlining process that allows you to get more immediate feedback from your peers about the directions you may want to take in your writing. In her work Remembered Rapture: The Writer at Work, author and cultural critic bell hooks writes about how her outlining process is improved through communication with others. When trying to write her autobiography, hooks recalls that memories “came in a rush, as though they were a sudden thunderstorm” (83). Often, she found that her remembering and categorizing process in recalling old memories of her younger life were best to “talk about” with others before she began writing (83).

For this exercise, you will want to return to the original bulleted list that you generated from your critical freewriting. If you find it helpful, you can use the example bullet list about text messaging we provided in the “Bulleting” section above.

Step #1

As you did with your visual outline, take some time to think about the central idea in your bulleted list that you created from critical freewriting. Highlight, underline or circle these main ideas in your bullets. You may want to use different color highlighters to differentiate between your starting, central idea and those that are supportive and expanding. Below, we have provided an example of coding in our created bulleted list by making starting, central ideas bold and expanding, supportive points italicized.

- Text messaging allows me to keep in touch with those I am close to that live far away and nearby me as well.

- Text messaging is a kind of writing that I use everyday in situations like when I’m bored with schoolwork.

- Text messaging is very similar to instant messaging in how it avoids weird silences that happen in face-to-face or phone conversations.

- Text messaging may create bad habits of passivity that might cause missing out on human interaction.

- Text messaging does not allow emotions to be heard like in someone’s audible voice.

Please note that the distinctions between your central and supporting ideas do not have to be finalized. Some initial thoughts may be part of your supporting points. Or you may still be in the process of solidifying an idea. This is perfectly fine. Just do your best to make as many distinctions as you can.

Take some time to code the bulleted list you generated from your starting, central ideas and supporting ideas.

In Step #1 of Auditory/Dialogic Generative Outlining, separating main and supportive ideas by marking them differently (highlighting, underlining, circling), helps you see generative connections you are making with your topic of text messaging. In looking over this list, there are many ideas you can explore about text messaging and its relationship to something else (ability to keep in touch with others, writing, instant messaging, bad habits of passivity, and emotions). Having these diverse connections about text messaging listed pushes you to see that there is no one, right answer that you need to explore in your writing. Instead, this invention step opens up many different possible connections for you to consider as you begin writing.

Step #2

For the next piece of this outlining strategy, work with a peer. In discussing the interactive nature of writing and communication, Elbow points out “there is a deep and essential relationship between writing and the speaking voice” (22). In speaking face to face with another student in your class that is writing the same assignment, you may find a higher level of comfort in conveying your ideas. However, you could also choose to share your bullets with another individual outside your class, such as a friend or family member.

Instruction #1 for the Writer: Look closely at your central, starting point(s) (coded in bold in the example above). Find a partner in class. Give them your coded list.

Instruction #1 for the Reader/Recorder: Read aloud each of the writer’s central starting points (coded in bold in the example above). Then frame a question for the writer that relates to their central points. An example question can be, “You have a lot of starting points that talk about text messaging and its relationship to something else (writing, instant messaging, bad habits of passivity, emotions). Why do these relationships to text messaging keep coming up in your ideas?”

Below is a list of three other example questions a reader/recorder might ask in relationship to the writer’s central starting points about text messaging. These example questions are offered here to help you think about what types of questions you could ask as a reader/recorder to a writer.

- The majority of your central starting points seem to express a strong point about text messaging with definite wording such as in “Text messaging allows me . . . ,” “Text messaging is a kind of writing . . . ,” “Text messaging is very similar . . . ,” and “Text messaging does not allow . . .” However, you have one central starting point that does not express certainty, and that one is “Text messaging may create bad habits of passivity . . .” Why is the opinion in this idea not as strong as your other starting central points? Why do you choose to use the word “may” here?

- In two of your central starting points, you seem to make a kind of comparison between text messaging and other forms of communication such as “writing” and “instant messaging.” Are there any other forms of communication that you can compare text messaging to? If so, what are they?

- Three of your central starting points (“Text messaging allows me to keep in touch . . . ,” “Text messaging may create bad habits of passivity . . . ,” “Text messaging does not allow emotions to be heard . . .”) appear to deal with human emotions and their relationships to text messaging. Is this relationship between human emotions and text messaging something you find interesting and want to further explore? If so, how?

Instruction #2 for the Writer: After the reader asks you a question about your central, starting points, start talking. While you want to try to remember the supporting details (coded in the example above in italics), do not hesitate to speak on new thoughts that you are having.

Below, we have provided samples of what a writer might say in response to each of the above reader/recorder questions.

- Well, I mean, text messaging may not definitely create bad habits that cause you to miss out on human interaction. At times, it could actually help you resolve something that might be tough to talk out with someone—like if you were in an argument with that person or something. Then, it might be easier for some people to text. But then again, text messaging is passive in some ways and does not allow you to talk with that person face to face. However, text messaging could be something that two friends use who live apart as a way to stay in touch because they can’t have human interaction due to geographical distance. So yea, I guess I used “may” to make sure I was not taking a decided stance on it. I’m still thinking through it, you know?

- Well, I mean text messaging can also be considered a type of reading that is a form of communication as well. You have to be able to know what certain things like “lol” mean in order to understand what you are reading in texts. Otherwise, you will not be able to respond to the person sending you the text. The reading you have to do in instant messaging and text messaging is really similar—you have to know the codes to use, right? And you can just keep on texting or instant messaging without all the awkward silences.

- Yea, I find that pretty interesting. I mean, text messaging can have certain inside jokes in it, but you don’t get to hear someone’s voice when texting. Also, you don’t get to give someone a high five, handshake, or hug. But yet, texting does allow you to keep in touch with some people far away from you. And texting is so much easier to use when trying to communicate with some friends rather than calling or visiting, know what I mean?

Instruction #2 for the Reader/Recorder: Write down what the writer is telling you about the question you asked, recording as much as you can on a sheet of paper. After you have finished taking notes, look back over what the writer has given you as supporting points (coded in the example above in italics) in his/her highlighted bulleted list. Check off ones that are mentioned by the writer. Then hand back the original paper with your check marks.

If you look at the samples above (under subheading Instruction #2 for the Writer), you would most likely place check marks next to the following ideas that were original supporting points of the writer. While you would not have written everything the writer said word by word, your notes should be able to provide you with his/her original, supporting points. These are listed below from the sample, and you could place check marks by them.

- missing out on human interaction

- avoiding weird silences

- you can’t hear someone’s voice when texting, but you can keep in touch with those that live far away

Instruction #3 for Writer: Look through the recorded notes your reader/recorder took about what you referred to in regards to the question the reader/recorder asked. Reflect on what you may have talked about that was originally not on your list.

Here, if you refer back to the samples above of the writer talking aloud (under subheading Instruction #2 for the Writer), you can see that much new information has been generated. Once again, the sample is not as detailed as what the reader/recorder would have written down. However, you should still be able to look through what the reader/recorder hands back and see new information that you generated while talking aloud. In our examples, this new information is listed below:

- text messaging might help you resolve something with someone else such as an argument

- reading is another form of text messaging communication, and you have to know the code of texting in order to read it

- text messaging can have certain inside jokes in it between people that are close

Now make sure to switch your roles as writers and readers/recorders once so each of you can have the benefit of this exercise.

You will uncover more specific supportive details in this invention exercise. You also may find that talking freely about your starting, central idea(s) can push you towards encountering new supportive details that come about from physical dialogue with a peer who is asking questions about your ideas. As bell hooks points out in recalling salient moments of her past, you can ignite productive reflection on ideas through talking them over with someone else.

In openly dialoguing with and also listening to a partner during this process, you will actively invent new supporting ideas as well as reinforce ones you find important about your topic. Talking through the ideas that come to mind as you dialogue with your partner is a way to experience more spontaneous invention. On the other hand, in asking questions and listening to a partner as he/she speaks, you are helping someone else invent—much like the diverse tools did for DeWitt’s father as he invented. In participating in invention that is collaborative, you are giving your writing peer support as he/she generates new ideas. This activity situates invention as a social, interactive process that can help you see many different directions you can take with a subject in your writing.

Reflection

In looking back over your experiences as both a writer and reader/ recorder, it will be helpful to reflect on what you learned in your dialogue process. We have found it useful for students to spend time writing about their ideas after talking them over with someone. Here are some questions you might consider asking as a writer:

- What did you learn from verbalizing your ideas?

- How might dialogue enable you to conceptualize and organize the structure for an essay topic?

Conclusion

When student writers are given the space and tools to be critical thinkers and writers, we have learned that they have a greater stake in the knowledge that they produce, recognizing their value as contributing members of the university. Invention in the writing process is not just about exploring ways into your writing, it is about also developing new ideas within ongoing academic conversations in an intellectual community. The strategies we offer for writing invention are by no means to be seen as individual, exclusive exercises in and of themselves. We have arranged them in sequence so that you might understand invention as a process of taking practical steps that work collectively in developing your reading and writing skills. As a college writer, you will find that not all conversations are alike; some require you to use a repertoire of rhetorical moves that are less formulaic and more complex. We hope that this chapter has demonstrated writing as an ongoing process of discovery, where developing multiple approaches to analyzing texts in your reading process also provides you the opportunity to learn multiple invention strategies for writing effectively.

Discussion

- How have you generally started your own writing assignments? What worked and didn’t work for you? Are there any ideas you have for invention in writing that are not in this chapter that you would like to add? What are they, and do you think they could help other students?

- Out of the new invention strategies you have learned in this chapter, which do you think would be most helpful as you transition into writing in higher education? Why do you think the invention strategy you choose would work well and in what way do you see yourself using it?

Works Cited

Anzaldua, Gloria. Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza. Aunt Lute Books, 1999.

DeWitt, Scott Lloyd. Writing Inventions: Identities, Technologies, Pedagogies. New York: SUNY P, 2001.

Elbow, Peter. Writing With Power: Techniques for Mastering the Writing Process. NewYork: Oxford UP, 1981.

hooks, bell. Remembered Rapture: The Writer at Work. New York: Henry and Holt Co.,1999.

- This work is licensed under the Creative Commons AttributionNoncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License and is subject to the Writing Spaces Terms of Use. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/us/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, California, 94105, USA. To view the Writing Spaces Terms of Use, visit http://writingspaces.org/terms-of-use. ↵