4 Defining Social Problems

Learning Objectives

In this chapter you will:

- Explain the difference between “objective” and “subjective” definitions of social problems.

- Define “claimsmaking” in social problems.

- Identify the mechanics of a claim.

Up to this point, I’ve been throwing around the term “social problems” without offering a proper definition. So, what is a social problem?

I’m going to give you a completely cliché and annoying answer: that depends!

On the one hand, we can think about a social problem as a condition that harms society or conditions that undermine well-being. This is an objectivist definition, which is based on objectively measurable characteristics of conditions. Through an objectivist lens, something becomes a social problem when it reaches a threshold of widespread or severe harm.

However, there are some limitations with an objectivist approach to defining social problems. Some things that cause great harm inspire little concern and action, while other things that cause relatively limited harm inspire a great deal of concern and action. Additionally, things that are considered problematic change over time, with some things that were common and accepted in the past inspiring great concern today. Even when people agree that a condition is harmful, they may offer very different explanations of what makes the conditions harmful, such that completely different characterizations of the problem emerge. It’s really rather messy!

Some sociologists argue that these limitations make a subjectivist approach ideal for defining social problems. That is to say that a condition can be considered a social problem if people believe it is harmful, regardless of any actual measure of the harm the condition causes (Best 2021). A subjectivist definition of a social problem is based on people’s beliefs and reactions rather than a measurable trait.

Considering the difference between the objective characteristics of troubling conditions in society and the subjective interpretation of those conditions is important because it highlights the fact that social problems are a product of social processes. Things become social problems because people care about them deeply and launch organized, effective campaigns to put troubling conditions on the public’s radar and persuade others to act. Social problems must be made to mean.

The study of meaning making around social problems is the business of sociologists interested in social constructionism. This theoretical perspective can get a little heady, but it’s worth putting on your critical thinking hats for a moment and thinking deeply about, well, your thinking.

The Social Construction of Reality

According to Peter Berger and Thomas Luckmann (1966), who wrote the book on social constructionism, most human behavior is determined not by the objective facts of a given situation but by the system of meanings and habits people attach to observed conditions. In turn, the structures of law and institutions that provide services in a society, social roles and statuses, valued cultural traditions, popular leisure activities, norms for polite social conduct, and many other aspects of our everyday lives that seem like fixed social facts are better understood as products of routine human interaction.

“The reality of everyday life is taken for granted as reality. It does not require additional verification over and beyond its simple presence. It is simply there, as self-evident and compelling facticity. I know that it is real” (Berger and Luckmann 1966: 23).

Through our interactions with one another – telling stories, participating in rituals, scoffing at weirdos – we give meaning to and impose values on objective conditions and observable events in our lives, actively creating the conditions that comprise our reality. But we’re typically not attending to this process consciously. Instead, we’re responding to a collection of taken-for-granted social habits that pattern our everyday lives.

If we had to stop and think about the reasons behind everything that we do daily, we’d never get anything done. Having mental shortcuts helps us get on with the business of living, but they come with some liabilities. We’re more likely to make biased judgements about people because we think we can size them up with a glance – oh, she’s one of those types! We’re also more susceptible to manipulation if we’re not thinking about how someone is trying to activate our dramatic instincts or persuade us. So, besides giving you a headache, thinking about your thinking – as well as how someone wants you to think – is an important component of developing the critical thinking skills you need to navigate a 21st Century information environment.

Making Social Prolems

Claimsmaking is a process in which people concerned about a troubling condition make assertions that a problem exists and attempt to persuade public audiences that they ought to be concerned, too (Best 2021; Loseke 1999). In the 21st Century information environment, it easy to amplify claims about troubling conditions using digital communication networks. Email listservs and social media give claimsmakers access to broad audiences with the click of a finger. Forget knocking on doors or paying for expensive glossy mailers. Today all you need is an Instagram account to raise a ruckus.

With the heightened ability of claimsmakers to circulate alarming rhetoric about social problems, it’s important to be able to critically analyze claims so that we can avoid reacting emotionally and instead rationally assess the merit of a claim. To learn to do this, we’ll consider the typical structure most claims follow, persuasive characteristics of claims, and we’ll look at a few recent examples of the uses and abuses of statistics in claimsmaking activity.

There are sociologists who have built entire careers out of rhetorical analysis, studying the persuasive claimsmaking activity around social problems. Their work provides a helpful guide in breaking down the typical structure, or pattern, that claims about social problems follow.

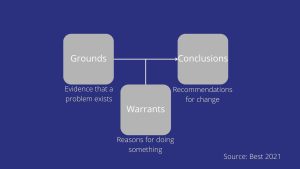

Joel Best (2021) breaks the anatomy of successful claims into three parts.

Grounds are statements that warn us about the severity or scope of a problem by telling us who is affected, how, and painting a picture of the extent of harm experienced (Best 2021: 32). To establish the grounds of a claim, claimsmakers must provide a typification of the problem for us. Due to the complexities of living in modern society, we can’t possibly have direct experience with everything in our environment. Instead, we rely on typification to provide pre-formed images of typical things we do have some direct experience with – mean dogs, bossy women – and we mentally lump things we haven’t directly experienced into categories based on things we are familiar with. Loseke argues, “Claims must convince audiences that a particular type of condition [is] at hand, that is has a particular cause, that it’s frequent, and that its consequences are troublesome (1999: 72-73, emphasis in original).

So, aside from establishing that a problem is of a certain type, the grounds of a claim are also going to provide some information about who is affected (the victim) and who is to blame (the villain), and they are probably going to include a statistic, or number, that demonstrates that the problem is widespread or affects many people (Best 2021). This is not going to be a neutral number. It is going to be a really big number that makes the issue seem really bad and looks highly official. More on that in a minute. Finally, in establishing the grounds of the problem, claimsmakers will give it a name that serves to both reinforce the problem’s typification and give us a nifty phrase for talking about it – a hashtag or handle for the issue, if you will.

Warrants are statements telling us why something ought to be done about the problem and typically appeal to broader ethical or moral principles as they issue a call to action (Best 2021: 37). The warrants of a claim are at the heart of its persuasive action and do the heavy lifting in generating a sympathetic response to claimsmaking activity. Warrants rely on the characterization of victims and villains established in the grounds of a claim and are more successful at inspiring sympathy when the victim is a person in a “higher moral category” (Loseke 1999: 76), such as a devoted churchgoer or a hard-working student, who has been harmed through no fault of their own. In contrast, it’s really hard to inspire sympathy for victims who are socially deviant – undocumented immigrants, drug users, sex workers – because they are violating moral and legal principles of our society, regardless of the harm they may experience through various conditions of their lives. Warrants, then, contribute to the work claims do to typify problems for us by providing a narrative, or story, about the problem that persuades us to see the issue as morally troublesome and worthy of corrective action.

Conclusions tell us which action(s) claimsmakers think should be taken to resolve the troubling condition (Best 2021). Conclusions are a key element of the persuasive argument made in a claim, providing recommendations for action and policy. It’s not enough to just convince people that the problem exists, as hard as that work may be. Claimsmakers who fail to convince their audiences that action is both needed and possible will make little progress in resolving the problem (Loseke 1999). Successful claimsmakers will therefore provide direction for the moral outrage they have stirred up by holding rallies or demonstrations, circulating petitions to sign, advocating for changes to laws or institutional policies, collecting donations, and so forth.

The next time you encounter alarming news about a widespread, morally troubling problem that makes you want to Snap at all your friends, hit pause and take a closer look. Recognizing the structural elements of a claim helps dislodge our dramatic instincts and kicks our critical thinking skills into gear, enabling us to move from emotional reactions to analytic reasoning. I’m not suggesting that you shouldn’t care about social problems, but I am pointing out that there are a whole lot of alarming claims being made at a given time, some of which call for quite drastic action. Before you hop on a bandwagon, maybe take a minute! Be aware that someone is trying to persuade you and think about what they want from you and why. Do some additional digging and make sure you’ve got the basic facts, starting with a critical examination of that statistic I mentioned earlier.

In Sum

In this chapter we’ve unpacked the social construction of social problems by discussing how social problems are brought into being as people concerned about troubling conditions:

- Make assertions, or claims, that a condition constitutes a problem.

- Work to disseminate their assertions and gain sympathetic audiences through claimsmaking activity.

- Make recommendations for actions and policy changes intended to help improve the troubling condition.

The public has a limited capacity to care about social issues, so claimsmakers must compete for attention, sympathy, and support. Claims that resonate with broad audiences because they successfully dramatize a situation or effectively relate to issues that people already care about may have a competitive edge, cutting through the clamor to become understood as social problems. However, if claimsmakers fail to attract sympathetic attention and inspire audiences to act, their issue will fall to the wayside regardless of the extent of harm the issue may objectively cause.

Claimsmaking is an inherently persuasive activity that has been amplified in recent years, which contributes to the feeling that everything is going to Hell in a handbasket. We are constantly confronted with alarming statistics about social problems, some of which are presented in misleading ways intended to align our view of the problem with that held by claimsmakers. For the sake of our sanity, it therefore serves us to hit pause and activate our analytic thinking when we are confronted by claims. Breaking a claim into its components helps us step back and think about the persuasive purpose of the claimsmaker so that we can make rational, informed decisions instead of reacting emotionally.

References

Berger, Peter L., and Thomas Luckmann. 1966. The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge. New York: Anchor Books.

Best, Joel. 2021. Social Problems 4th edition. New York: W.W. Norton.

Loseke, Donileen R. 1999. Thinking About Social Problems: An Introduction to Constructionist Perspectives. New York: Walter de Gruyter, Inc.

A perspective that bases assertions on observable, measurable characteristics (Best 2021).

A perspective that bases assertations on what people think exists, rather than what can be observed (Best 2021).

A theoretical perspective assessing how subjective meanings become objective facticities (Berger and Luckmann 1966).

The act of bringing a troubling topic to the attention of others (Best 2021; Loseke 1999).

A statement that makes a persuasive argument that a condition is troubling and needs to be fixed (Best 2021; Loseke 1999).

The people who are making the claims (Best 2021; Loseke 1999).

The study of persuasion (Best 2021: 30).

Assertions of fact arguing that a problem exists and offering supporting evidence (Best 2021: 32).

Pictures in our heads of the types of things that we have direct experiences with, which we use to make inferences about similar things we have no direct experience with (Loseke 1999: 16).

People who experience harm through no fault of their own and deserve our sympathy because they are basically good (Loseke 1999).

People who cause harm for no good reason and are therefore an object of moral condemnation (Loseke 1999).

A number often used in a claim to establish that a problem is widespread or frequently occurring (Best 2021).

The title given in to a problem in a claim to reinforce its typification and establish language for speaking about it (Best 2021).

Moral appeals that justify doing something about a troubling condition (Best 2021: 37).

Statements that specify what should be done about the perceived problem (Best 2021: 39).